In West Lake Hills, work crews for Travis County Water Control and Improvement District 10 have been installing larger water lines along several streets to carry higher pressure to upgraded water hydrants.

And in Steiner Ranch, a small group of volunteers are recruiting homeowners to audit their property to determine how much debris and overgrowth should be removed from their landscape.

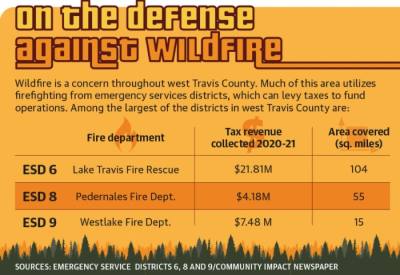

On the surface, all of these activities throughout west Travis County appear unrelated, but they are all designed to prevent a common threat—devastating wildfire. In western Travis County wildfire is an ever-present threat because of the rolling, hilly landscape, close proximity between homes and acres of nearby trees found in areas like the Balcones Canyonlands National Preserve.

As of late March, despite sporadic rain, Travis County was under a burn ban in part because of the amount of dead and dying material left from the February winter storm, said Will Boettner, wildfire specialist with the Travis County Fire Marshall’s office.

“Right now there is an excess of fuel,” he said. “Our woodland areas now have a surplus of dead and dying stuff from the ice storm. There is more material down than normal because of that ice storm.”

It would not take much wind and hot embers from a property owner burning debris in a small burn pile to create a sudden, serious problem, Boettner said.

“That’s what we worry about the most, is someone who is burning something that is considered not that big of a deal, and then there is an escape,” he said.

An escape is what firefighters call it when wind whips up burning material and sends hot embers flying through the air, he said.

“These embers are very hot, and they can stay hot while floating along with the wind,” he said. “They can travel a quarter of a mile on a normal day and start a fire.”

At Lake Travis Fire and Rescue, Wildfire Mitigation Specialist Chris Rea and Lt. Adam Griggs said an event like what Boettner described is what firefighters call an “ember storm.”

Hot embers settling into a thickly wooded area can easily ignite small twigs and grasses and then spread fire to taller material, what firefighters call “ladder” fuels that allow flame to reach into the upper tree tops.

Thinned lines of trees, known as a shaded fuel break, are being built under the direction of LTFR in Hamilton Greenbelt and are designed to prevent fire from easily traveling through a wooded area. Gaps and clearings between trees slow a potential wildfire by keeping it close to the ground and preventing it from quickly climbing into high branches, known as the crown, where it can then jump from tree to tree, said Rea. A thinner, less dense line of trees also makes room for firefighters to set up firefighting equipment, Griggs said.

“If there is a crown fire, there’s not much we can do unless we have heavy equipment,” Griggs said.

The work in Hamilton Greenbelt is part of the Wild Land Fuels Mitigation program. In addition to removing potential fuel for a fire to spread quickly, a goal is to move dense trees 30 to 100 feet away from private property lines to offer homes protection, according to Rea. Rea keeps the city of Lakeway, which is funding the project, updated on progress clearing and thinning trees in the Hamilton Greenbelt. The greenbelt is made up of two sections, totaling 75 workable acres out of 90 acres. Clearing debris and removing overgrowth has a total budget of $350,000, according to city documents.

“This is probably the biggest job the city has ever done as far as land management is concerned,” Rea said. “It’s one of the most centrally located greenbelts here in Lakeway ... and since it’s so centrally located, if a fire started in this greenbelt, the embers could do a lot of damage, not only in the greenbelt, but any where a mile around the greenbelt.”

Concern about wildfires in western Travis County took on particular urgency following the destructive fires that occurred in Travis County in September 2011, Rea said. Notable was a fire in Steiner Ranch that likely started, according to a Travis County Fire Marshall report, from sparking power lines and went on to destroy 23 homes.

Preventing devastation like this has the attention of firefighters in West Lake Hills as well. Firefighters with Travis County Emergency Service District 9 are in the process of gaining increased water pressure, up to 2,000 gallons per minute, thanks to a series of infrastructure upgrades from a $45.96 million bond that voters approved in 2015 for Travis County Water Control and Improvement District 10.

Since then infrastructure improvements and the associated administrative tasks have taken place in areas along Bee Cave Road, Little Bend Drive and Red Bud Trail, WCID 10 General Manager Carla Orts said. Wildfire preparedness was among the goals of the improvements.

“When we were asking our engineers to design the upgrades, we were aiming for 2,000 gallons per minute because that enables our firefighters to use the water cannons on top of their trucks, which gives them the best opportunity to fight a fire,” Orts said. The push for the WCID 10 bond project came not long after the Bastrop Complex and Steiner Ranch wildfires that occurred in the fall of 2011, Orts said.

Today, a few Steiner Ranch homeowners keep those events in mind when they advocate to their neighbors the need to assess homes for vulnerability to the ember storms that can transition a wildfire to a structure fire.

Steiner Ranch resident Bill Hamm heads up the Steiner Ranch Firewise Committee. Firewise is an educational program sponsored nationwide by the National Fire Protection Association. He said he became actively involved in fire prevention after learning about the devastation from the 2011 fire.

“I didn’t realize what a chaotic event that Steiner fire was,” he said.

He and fellow committee members regularly distribute information about fire prevention in Steiner Ranch’s neighborhood newsletter. He said he urges neighbors to assess the dangers of fire around their home. It is an ongoing effort.

Hamm said he figures only 1% of the homeowners in Steiner Ranch have evaluated the threat of wildfire to their property.

“This is a collective action because if your neighbors’ house burns, chances are yours will, too,” Hamm said.

Much of Steiner Ranch lies outside of the Austin city limits. For this reason, Steiner and other communities like it, such as Long Canyon, River Place and Spicewood, are examples of a current legislative priority for state Rep. Vikki Goodwin, D-Austin, who filed a bill in the current Texas legislative session concerning wildfire safety.

The bill, pending in the Texas House Land & Resource Committee, if passed into law, would give counties the power to implement wildfire prevention requirements in unincorporated areas of a county. The requirements are part of what is known as the International Wildland-Urban Interface Code.

Goodwin said she is working with area emergency service districts to update the bill to assure it works in unison with current fire prevention codes in place.

Examples of code requirements include ensuring adequate water supply in the construction of a home and requiring appropriate street widths to accommodate fire fighting equipment, Goodwin said.

“It’s equally important to get it outside of the city limits because the wildfire isn’t going to care if it’s in the city or not,” she said.