“We live on the lake. We play in the lake, and we have a dog who loves the water,” Langerock said.

However, this spring, Langerock said she is keeping her family and dog out of the water in an effort to avoid a potentially harmful blue-green algae bloom. In late February, the Lower Colorado River Authority—the nonprofit utility agency in charge of Lake Travis and surrounding lakes—reported that four dogs became ill after swimming in the Hudson Bend region of Lake Travis.

LCRA promptly conducted testing on water and algae samples from the area. Though initial reports did not indicate the presence of any harmful substances, LCRA issued a news release March 9 confirming that more extensive testing conducted at laboratories in Austin and Florida revealed toxic blue-green algae in Lake Travis.

Blue-green algae blooms are known to cause illness or death when the algae or surrounding water is consumed by dogs or other animals. Locally, blue-green algae in Austin’s Lady Bird Lake resulted in the death of at least five dogs in 2019.

As a result, LCRA encouraged pet owners to keep their dogs out of Lake Travis—a precaution still in place as of this edition’s April 5 press date.

“We can’t stress this enough–out of an abundance of caution, do not let your dogs touch or ingest algae from the lakes,” John Hofmann, LCRA executive vice president of water said in a news release. “We know even a little toxicity from blue-green algae can be harmful or even fatal to dogs.”

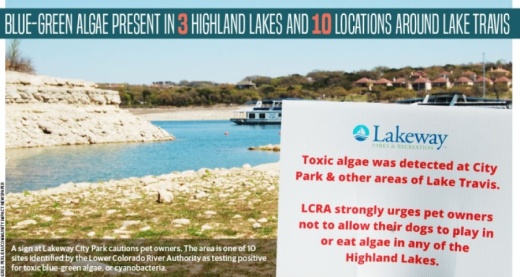

Additional test results received by LCRA on March 12 revealed the presence of blue-green algae at 10 locations on Lake Travis including, Lakeway City Park, Travis Landing, Mansfield Dam Park, according to a news release from LCRA.

The release also reported that in total five dogs had become ill and two had passed away after swimming in the Travis Landing, Hudson Bend and Comanche Point regions.

On March 23, LCRA informed the community that the harmful algae had emerged in other Highland lakes. Low concentrations of the toxic algae were identified on the shoreline and boat ramp at Inks Lake State Park, as well as Lake Marble Falls.

LCRA declined to elaborate on the blue-green algae incidents beyond the organization’s news releases. Community Impact Newspaper was told the organization did not have an available representative to answer questions.

Langerock said the reports have raised concerns for residents and pet owners throughout the Lake Travis region.

While the events have alarmed nearby residents, the presence of this organic material is not unique to the Highland Lakes chain, according to Hofmann.

“Blue-green algae are common in Texas Lakes, and it is not easy to predict if or when algae will start producing toxins,” Hofmann said in a March 23 news release.

In fact, blue-green algae can be found in a majority of water sources, according to Jill Csekitz, a technical specialist within the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality’s Water Quality Planning Division.

Similar reports have emerged in Lake Erie in Michigan and in lakes throughout the country but despite the apparent commonality of blue-green algae, Csekitz said there is still a public misunderstanding on the topic.

What makes blue-green algae toxic?

Aquatic scientists are learning more about why blue-green algae blooms occur and what makes them toxic, Cskeitz said.

“Blue-green algae is kind of a misnomer,” Csekitz told Community Impact Newspaper.

Though the term is frequently used by both the public and scientists, Csekitz said the correct name of the material found in Lake Travis is cyanobacteria, and it is one of the oldest known organisms.

Cyanobacteria are not technically algae but the organisms do share similar characteristics and appearances. The bacteria can exist in thick clumps along a lake’s shorelines and often appear bright green, blue or at times red in color.

Most notably, cyanobacteria are photosynthetic and produce oxygen, meaning they need light and nutrients to grow, according to Csekitz, who said algae share these same traits.

Additionally, not all cyanobacteria are harmful to animals or humans. There are around 6,000 different species.

“In general, cyanobacteria are found in most, if not all, aquatic environments. Any place where you have light and nutrients you can find them, but not all are toxin producers,” Csekitz said.

However, the bacteria can be dangerous when producing cyanotoxins, which can be released into the surrounding water source. The type of cyanotoxin found in Lake Travis is known as dihydroanatoxin-a, which according to Csekitz is a less commonly found form.

Test results indicated dihydroanatoxin-a within the algae from Lake Travis. Testing also revealed low concentrations of the toxin in water samples from the Hudson Bend, Comanche Point and Travis Landing areas of the lake.

However, even small amounts of this toxin can be fatal to dogs and animals when the algae or water is ingested, according to an LCRA news release. Common symptoms in dogs can include excessive drooling, vomiting, foaming at the mouth, respiratory paralysis, among others.

The blooms that have occurred in both Lake Travis and the city of Austin have only impacted dogs, which are more likely to ingest water and algae while submerged in the lake.

LCRA has not indicated any current threat to humans or drinking water, which is regulated by TCEQ. Additionally, the city of Austin stated on its blue-green algae website that the threat to humans is currently low.

Still, in an effort to avoid potentially toxic blue-green aglae, lake-goers should avoid areas with stagnant water and should never handle algae around the lake, Csektiz said.

What causes cyanobacteria to become toxic is not immediately known or presented within lab testing, which can create a challenge for water agencies such as LCRA and ecologists, according to Csekitz.

There are various factors that contribute to harmful algae blooms, which include but are not limited to temperature, light, ecological competition, nutrients, agricultural runoff and even the presence of Zebra mussels, per a statement from TCEQ.

“Those can all play a factor but we don’t know exactly what makes them produce toxins at particular times,” Csekitz said.

Additionally, it is unknown whether the blue-green algae spread from one region of Lake Travis to another, or if individual and isolated blooms occurred throughout the Highland Lakes chain.

The previous blue-green algae incidents stemming from Austin’s Lady Bird Lake occurred in the summer and were linked to hot and arid weather conditions. Less rainfall, high temperatures and extended daylight are contributing factors to harmful algae blooms, meaning summer is typically the most high-risk season.

However, the reports from Lake Travis occurred directly after Texas’ winter storm, at a time when the region was still recovering from sub-freezing temperatures.

“The event that’s occurring now doesn’t fit that bill. It’s colder. Lake Travis is one of the clearest reservoirs in the state,” Csekitz said.

As a result, Csekitz said the community should stay vigilant against blooms year-round.

For community-members like Langerock, this advice raises many questions. She said prior to a couple of months ago, she never heard the term blue-green algae, much less worried about it.

It is unclear whether cyanotoxins have existed in Lake Travis before or if LCRA has ever received reports related to blue-green algae prior to February.

Notably, the first reported incidents involving blue-green algae within the city of Austin occurred in 2019, according to Brent Bellinger, an aquatic ecologist with the city’s watershed protection department.

While there is speculation and emerging environmental studies suggesting that the presence of blue-green algae may be on the rise, Bellinger said ecologists are also learning more about the bacteria and how to accurately detect it.

Increased interest

Though Bellinger said he is not aware of any cases of toxic algae within the city of Austin prior to 2019, that does not mean cases did not exist. Locally, residents and local veterinarians have grown more aware of blue-green algae, which he said could lead to increased reports.

“In the past, perhaps there was an incident of an animal getting sick and it was just misdiagnosed or it wasn’t diagnosed or pursued at all,” Bellinger said.

Furthermore, Bellinger said ecologists have developed an increased understanding of harmful cyanobacteria and the symptoms associated with consuming the toxins. Still, he acknowledged the widespread speculation that incidents of toxic cyanobacteria blooms are increasing globally.

“In general, the [studies indicate] that the rise in these toxic blooms globally is related to more people moving to urban environments,” Bellinger said. “You have more runoff, development, agricultural practices [and] over-fertilizing.”

These factors join together in favor of toxic cyanobacteria growth, according to Bellinger. However, LCRA has not reported a direct cause for the recent Highland Lake blooms.

Notably, test results received by LCRA on March 23 indicated lower levels of cyanotoxins near Hudson Bend compared to the two previous tests taken earlier in the month. Though, LCRA did not report the use of any treatment methods.

Despite the decrease in toxin concentrations, Hoffman told residents in a news release “the key is not to let your guard down,” in a news release. “Our tests show what was present at the specific site we tested on the day we took the samples but conditions can change.”

Moving forward, a possible plan to tackle or prevent blue-green blooms in Lake Travis, Inks Lake and Lake Marbles Falls has not been shared by LCRA or other entities.

In the meantime, as LCRA continues to monitor the situation, Langerock said she hopes to see local authorities work to inform the surrounding community on this issue and potentially develop online resources and further communication methods.

Csekitz said the public is doing the right thing by asking questions and staying up-to-date on information released by LCRA. Residents’ vested interest in toxic algae blooms further drives new studies, new laboratories and research, which gives ecologists a “leg-up” on combating these incidents.