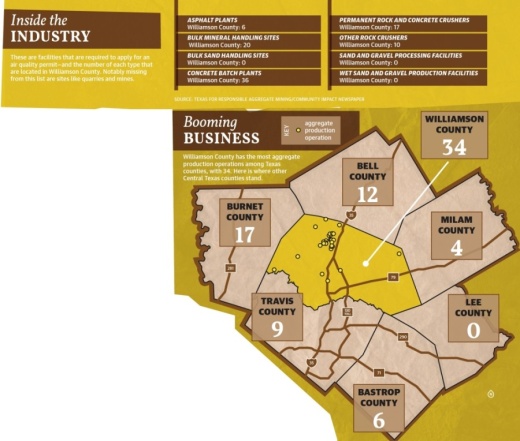

The county currently has 34 such operations, according to Texas Commission on Environmental Quality data, and these operations are continuing to grow at a rapid rate across the state.

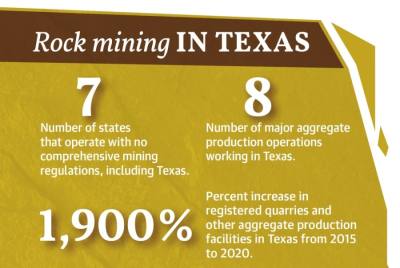

From 2015 to 2020 the estimated number of registered quarries and other aggregate production facilities operating in Texas jumped from about 50 to more than 1,000, many of which are located in Central Texas—home to some of the fastest-growing counties in the country, according to Texas for Responsible Aggregate Mining data.

“This has all just exploded in the last couple of years. It’s unbelievable how fast this [industry] is running,” TRAM spokesperson Fermin Ortiz said. “But we’ve got to figure out a way to make it better and more responsible because we’re not going to stop it.”

As Williamson County continues to be one of the highest-growth counties in Texas and home to a few of the most rapidly growing cities in the state according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the aggregate production operations, or APOs, supply needed construction materials as well as jobs, Ortiz said.

He added that APOs being located near major growth sectors also makes the most business sense, as suppliers need to be near buyers in order to reduce costs.

But the issue does not lie with their existence, Ortiz said. Instead, it is the damage the industry could cause if it remains deregulated.

For example, air quality can be hindered as blasts often send dust into the air that is then breathed in by community members, potentially negatively impacting their health. The APOs, often referred to as a quarry, also use high amounts of water at about 50 gallons of water per ton of aggregate mined, according to TRAM data. A small mine can produce a couple thousand tons a day, Ortiz said, adding that he would like a commitment by quarries to use recycled water for this reason.

Heavy truck loads also tear up roadways, which are repaired at the taxpayer’s expense, and the constant noise and odor, as well as destruction of natural habitats, can be a detriment to quality of life, Ortiz said.

“There are good ways to do good business, you don’t have to take the shortcuts and take the quick profits,” Ortiz said. “If you want to stay in business long term, you want to be a good neighbor, [and] you want to do it right.”

Ortiz, through TRAM, is working to reduce the negative impacts of quarries through regulations and legislative measures. He said he feels it is Texans responsibility to hold large mining businesses accountable, particularly those who are interested in making as much money as possible regardless of the negative health and traffic impacts it may cause.

“This is a non-partisan issue. This is about what we leave to our great-grandchildren and children going through generations,” he said. “The regulations that we do or don’t have today are going to negatively impact the future, and it’s our responsibility to all join together to push back and have some sensible regulations to slow down the greedy [operators].”

Community concern

Williamson County resident Tom Brothers’ issues with the APO kitty corner from his property did not arise until CC Aggregates LLC took over the quarry about six years ago.

Brothers said in his 25 years of living in his home, previous quarry owners were relatively respectful, notifying him of loud blasts and fixing any damage his property incurred. But when CC Aggregates took over, he began to notice negative impacts on his quality of life.

Now, Brothers said he lives with loud mining sounds that sometimes go late into the evening, blasts with limited warning and a dust-covered home. He added that each day at least 100, if not more, loaded trucks drive well above the posted 25 miles per hour speed limit on the small country road in front of his property, making him fearful of being in a car accident.

“I’m not against business, I’m not against people making money, but I am against people driving me out of my home making it where I can’t breathe, making where it’s unsafe for me to leave my home and running all kinds of days and nights and all kinds of hours,” Brothers said.

While Brothers also noted foundational issues on his home and lime build up on his faucets, he does not have proof it is due to the quarry across the street.

CC Aggregates did not respond to a request for comment from Community Impact Newspaper.

Williamson County resident Michael Spano said blasting in the quarry has shaken his and his neighbor’s homes hard enough that windows rattle and picture frames fall from the walls.

Spano, who is also a spokesperson for Coalition for Responsible Environmental Aggregate Mining or CREAM, a local organization also seeking an increase to quarry regulations, said the blasts are also occurring more often and with little to no warning.

He added that beyond its impact to their environment, health and quality of life, he is also concerned of what it could mean for their property values. All of these combined has led to formation of local coalitions such as CREAM, across Texas, Spano said.

“I think a lot of people are really starting to see the optics and feel the optics of it. And I think people are kind of tired,” Spano said. “As citizens, you just want to feel that someone is looking out for us and has our interests in mind.”

Booming business

Rock mining operations in Texas were deregulated in 2005 to allow for an increase in needed infrastructure and to create jobs, state Rep. Terry Wilson, R-Georgetown, said. Since then, it has grown into a $2.4 billion industry, according to TRAM data.

By deregulating, required permits through the TCEQ, the United States Army Corps of Engineers and Texas Parks and Wildlife, among others, were easier to obtain. In fact, from 2009 to 2019, 1,220 air quality permit applications from throughout Texas were submitted to TCEQ, to which 1,143 were approved, five were denied and 72 were withdrawn, according to TRAM data.

But even with the easy access to permits and a few regulations in place, Ortiz said there is limited oversight as regulatory agencies have been stripped of any significant power.

“Most of the regulatory bodies, as we have them in Texas today, are designed to give out permits,” Ortiz said. “The advantage is to the company unless they do something very egregious.”

Now, Texas is one of only seven states without a comprehensive mining regulation. This is what Wilson, who represents parts of Williamson, Burnet and Milam counties, would like to fix.

“It’s our responsibility to realize the significant change in the number of these quarries since 2005, and we need to adjust accordingly,” Wilson said.

Wilson said he intends to bring up several legislative measures on quarry regulations in the 87th Texas legislative session, which begins in January. One of the key initiatives he is in favor of is only awarding state contracts to companies in good standing.

Wilson said the state can identify best practices for companies and use it when selecting for government contracts. This will incentivize both the developers and suppliers to be companies known to work well within their communities.

“It’s just not about who can give us the cheapest bid, it’s about who can provide us a fair bid with a past performance of high quality,” Wilson said. “And the past performance is the key there.”

Wilson also said he would like to strengthen regulations on where APOs can operate. Texas is a property-rights state, meaning APOs can mine in between neighborhoods and near hospitals with no rules stopping them otherwise, he said.

This could not only have a negative impact on health but also quality of life, Wilson said.

Other required regulations Wilson and TRAM are seeking are rock conveyor belt covers to keep dust down, reduced hours of operation to cut noise pollution, and the installation of air quality control measures, among others.

Wilson, Ortiz and others recognize that it is not all APOs that operate as bad actors, in fact many do abide by self-imposed health and safety regulations, and that is something Jill Shackelford is working toward.

Shackelford, a former Central Texas quarry owner and operator who now consults nationally, said she believes it is the responsibility of the quarry owners to not only communicate but over communicate with the community around it by notifying them of blasting or changes and act as a good neighbor would.

This is something she emphasizes to all of her clients, she said.

“It’s an important responsibility for quarry operators to respect their community and their neighbor,” Shackelford said. “If they’re near neighborhoods, or whatever environment they’re operating in, they should respect those stakeholders, communicate appropriately and be transparent about everything they’re doing at their site.”