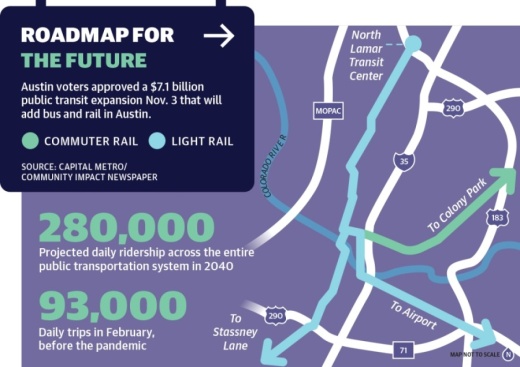

Voters responded by approving the $7.1 billion transit plan and a permanent tax increase. Out of more than 418,000 votes cast throughout the city, 57.9% approved.

At the start of 2020, residents needed only to drive on I-35 at rush hour to understand the city’s traffic woes. The average speed on the 8-mile stretch of I-35 from Hwy. 290 to Ben White Boulevard traveling south at 5:30 p.m. was 22 miles per hour according to 2019 data from the Texas A&M Transportation Institute.

The pandemic changed all that. Traffic subsided as many employees began working from home. However, Capital Metro asked voters to remember what life was like before COVID-19 and vote “Yes” to a tax hike in the middle of an economic recession, with unemployment in the metro more than double what it was last year.

“I think it’s very heartening and speaks well of the voters in Austin that they did have a vision for the future in making Austin a better place,” Capital Metro Board Chair Wade Cooper said. “It makes me proud to belong here.”

Capital Metro President and CEO Randy Clarke said the Central Texas region cannot efficiently move people around today, and it will only be more problematic in the decades to come as the population grows.

“I’m bullish on Austin, bullish on Cap Metro, bullish on transit. Traffic will be back; it’s going to be worse than ever. We are ultimately going to be a big release valve for this community when we’re done,” Clarke said.

The $7.1 billion plan voters approved is part of a larger $10 billion plan Capital Metro has outlined. However, the additional routes in the larger plan will only be built if more funding becomes available at some point in the future.

Sticking to schedule

While light rail construction is not set to begin until 2024, work is starting on Project Connect right away—beginning with putting the board in place that will oversee decisions to implement the program.The Austin Transit Partnership will comprise one Austin City Council member, one member of the Capital Metro board of directors and three community members—an expert in finance, an expert in engineering and construction, and an expert in sustainability and planning. Capital Metro’s board and Austin City Council are set to meet Dec. 18 to submit nominees for the ATP. The board will then meet for the first time Jan. 20.

Project Connect is not one investment on one timeline. Rather, it includes a package of various projects, each of which will go through a different approval process.

“There is not one federal project, approval or grant. We have a dozen-plus projects here,” Clarke said.

New bus routes and pickup services called “neighborhood circulators” could be the first tangible results Austinites see from their Nov. 3 decision. Dave Couch, Capital Metro’s Project Connect program manager, told the board of directors in September that the three new bus lines have advanced to the first phase of the Small Starts program, a $2.3 billion annual grant program from the Federal Transit Administration.

Those three MetroRapid lines—which will run more frequently and with fewer stops than traditional Capital Metro buses—will add 35.5 miles and 69 new stations to the transit agency’s bus network. According to Capital Metro, they are scheduled to be in place by 2024, with work starting in late 2021 or early 2022. A fourth MetroRapid line, the Gold Line, will run between Austin Community College’s Highland campus and the South Congress Transit Center; that could be built in 2024.

Chad Ballentine, Capital Metro’s vice president of demand response and innovative mobility, said staffers have identified three initial zones to add neighborhood circulators, or on-demand pickup services, in which customers living in a certain area can request a shared ride for $1.25 to connect with a main bus route.

Project Connect includes $3 million to create 15 circulators. According to Ballentine, Capital Metro aims to have boundaries finalized for new zones, including two in South Austin, by December.

The most significant and costly piece of Project Connect is still years down the road. The Orange and Blue light rail lines, set to connect riders from North Austin, South Austin and the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport to an underground tunnel downtown, could begin construction in 2024, with completion estimated for 2029.

Minneapolis recently went through a similar process. After approval from City Council in 2014, a 14.5-mile light rail line began construction in 2018 and is set to finish in 2023. A Capital Metro spokesperson said the overall timeline is comparable to Austin’s, but construction could start sooner locally than it did in Minneapolis.

The two light rail lines and downtown tunnel account for $5.8 billion of Project Connect’s total $7.1 billion cost. The third new rail, the Green Line—a commuter rail service between East Austin’s Colony Park neighborhood and downtown—will cost just $300 million.

The Green Line will run along tracks Capital Metro already owns, whereas to build light rail, Capital Metro will have to build completely new infrastructure.

Light rail is designed to move people through dense areas of town and therefore has more stops than does commuter rail service, which is designed to connect people from suburbs or areas outside of town to the heart of the city. The Orange and Blue lines combined have 25 proposed stops on their total route of roughly 18 miles. The Green Line has seven proposed stops on its approximately 9-mile route.

An uneven result

Although Project Connect passed by a comfortable margin of more than 66,000 votes, its support was heavily concentrated in the core of Austin, near the areas the light rail lines are proposed.All the precincts that voted against the proposition, save two, were located either west of MoPac or south of Slaughter Lane. The precinct with at least 100 votes that went most heavily against the proposition—with 70% voting against—is located in West Lake Hills near Toro Canyon Road. The precinct that leaned most heavily in favor, with 83% of votes, was located in West Campus, surrounding the intersection of 24th and Rio Grande streets.

Peck Young, who leads a nonprofit organization called Voices of Austin that opposed the plan, said he believes homeowners in West and South Austin voted “No” because they will be paying more in taxes without seeing immediate results.

Young, a longtime Democratic political strategist, said that although the campaign against Proposition A is over, he plans to continue voicing his opposition to City Council’s direction on other initiatives, such as its decision to reallocate public safety resources and its ongoing effort to rewrite the land code.

“This City Council got lost in the weeds a long time ago, and it ain’t going to get out of the weeds until [we] get new leadership,” he said.

While Young said Project Connect’s price tag, which raises the city’s property tax rate to 53.35 cents per $100 of valuation, turned off many voters, Cooper said he believes Project Connect passed precisely because Capital Metro went big.

“The public wanted to see something that would really move the needle: a regional vision, [a] multigenerational vision that would engender confidence that we were really going to make life better for everybody,” Cooper said.

Clarke called the Nov. 3 vote “a result of a 20-year conversation” in Austin. In 2000, voters denied a light rail plan by a slim margin, and in 2014, they rejected a second attempt by a much wider spread.

Mayor Steve Adler, who was elected six weeks after that second failed attempt, said it is “about time” Austin made public transportation progress.

“I’m just really excited and proud to be part of a city that is moving toward a future that is saying so dramatically that the status quo is not good enough,” Adler said.