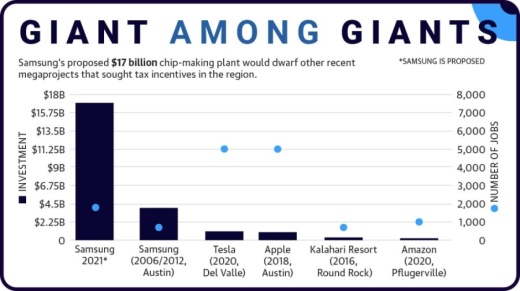

According to the documents, the plant would come with $5.6 billion in construction costs and $11.4 billion worth of machinery and equipment. Samsung promises to create up to 1,993 jobs, of which 1,800 carry an average salary of about $100,000. The plant would be the largest single investment in the Austin region and easily surpass recent billion-dollar projects such as Tesla’s Gigafactory in 2020 and the Apple campus, announced in 2018.

A 100% property tax reimbursement over 25 years would mark the most aggressive corporate tax break in Austin history. What it equals in actual dollars is unclear. According to the documents, Samsung already rejected a 10-year agreement offered by the city that included nearly $650 million in property tax and other incentives. The offer by the city is nearly six times greater than all five of its active economic incentive packages combined.

A Dec. 9 analysis on the project from Impact Data Source estimated a 20-year, 100% Travis County property tax reimbursement would be worth about $718.3 million. The analysis used the existing Travis County property tax rate of $0.374 per $100 in valuation. Austin’s current property tax is $0.535 per $100 in valuation.

Spokespeople from the city and Samsung have declined to confirm any information regarding the deal as of press time. Community Impact Newspaper specifically asked Samsung whether the widespread failure of the state’s energy grid following winter storms Feb. 14 would affect the company’s decision, but Samsung did not comment.

Incentive deals such as this are often negotiated in secret to protect the sides’ negotiating positions. The public is only brought in after an agreement is reached and brought to City Council for approval. Some experts and members of the public have questioned offering a large tax break to a corporation bringing only 1,800 high-skilled jobs to an already humming economy. The project also runs counter to the city’s own commitment to focus its incentive program on assisting small businesses.

“Trying to get the big company to relocate in your community is actually kind of the opposite of what most of these programs should be,” said Nathan Jensen, a government professor at the University of Texas whose research focuses on economic incentive policy. A delicate approach

Chapter 380 of the Texas Local Government Code allows communities to offer public money grants “to promote local economic development and to stimulate business and commercial activity in the municipality.”

Five of Austin’s eight active Chapter 380 agreements are with corporations, such as Samsung, Apple, Visa and the property manager of The Domain development. The investment on behalf of the five corporations totals roughly $4.5 billion.

Although the region has recently attracted several major investments, from Tesla and Apple to the relocation of Oracle and the expansion of Google, the city of Austin has not struck a major economic incentive deal since 2017, when pharmaceutical giant Merck agreed bring a $28.7 million lab project in exchange for tax rebates estimated at $856,000. Merck later pulled out of the deal. Tesla’s Gigafactory deal in 2020 was outside city limits and included no city of Austin incentives. Apple’s 2018 deal to build a second campus was within city limits but only received property tax incentives from Williamson County.

Jensen said tax incentives for economic development should focus on correcting market failures.

“What is [the market] not providing? There’s been some talk about food deserts. Maybe we should incentivize health care to come to our community or renewable energy,” Jensen said.

Austin political leaders have criticized the city’s deals as unnecessary. In 2016, the most recent data available, Austin paid $13.6 million in property tax rebates to seven companies, $9.9 million of which went to Samsung for its existing chip plant.

The latest Samsung deal represents the first test of the city’s new-look incentives policy. Rewritten in 2018, it sets a maximum incentive of 50% property tax reimbursement at five years for local expansion projects and 10 years for “external relocations.” However, the policy includes a crucial clause that allows consideration of “high-impact projects, unique developments and market competitive or other non-conforming projects” on a case-by-case basis.

Travis County is also revising its own incentives policy. In December 2019, the county adopted a strategy that recommends targeting small and medium-sized businesses. Earlier that year, county commissioners placed a moratorium on incentive deals after the Texas Legislature passed its 3.5% property tax revenue cap.

Sarah Eckhardt, county judge at the time, said the cap meant the county could not afford “preferential tax treatment” for wealthy corporate citizens.

However, the county has lifted the moratorium twice in the past year—to negotiate with Tesla, and, in January, to accept a tax rebate application from “Silicon Silver”, the name Samsung used in documents relating to the potential deal with the city.

The necessity of incentives

Ellen Harpel, an economic consultant and founder of the Virginia-based firm Smart Incentives, said incentive deals allow communities to address specific economic development goals, such as creating more middle-skill jobs, revitalizing downtown or diversifying the economy. “Incentives should never just be about winning a deal or completing a transaction ... It’s always connected to a larger economic development strategy; ... it’s foundational,” Harpel said.

Aside from the failed Merck deal, Austin’s most recent corporate tax incentive deal was struck with Apple in 2012. Before Tesla in 2020, Travis County’s last deal was struck in 2014 with Charles Schwab. Most of Austin’s agreements, and half of Travis County’s, were reached between 2010 and 2012.

John Hockenyos, founder of economic firm TXP Inc., which consults the city on such deals, said during that time, governments were focused on recovery during the Great Recession. Hockenyos said the economy has since been “pretty darn good.”

Timothy Bartnik, a senior economist with the UpJohn Institute of Employment Research, said the influence of tax incentives in luring companies is “exaggerated quite a bit” and that governments should refrain from these deals unless they are in a distressed regional labor market. His analysis of tax incentive deals across the country showed companies that received government tax incentives were, in most cases, coming anyway—especially when the project was a local expansion.

Documents show Phoenix, Genesee County in upstate New York and South Korea are also contenders for the plant. Austin already hosts Samsung’s largest manufacturing plant in the U.S. In October 2020, the company bought more than 257 acres of land right next to the existing plant and rezoned most of it to allow for industrial use.