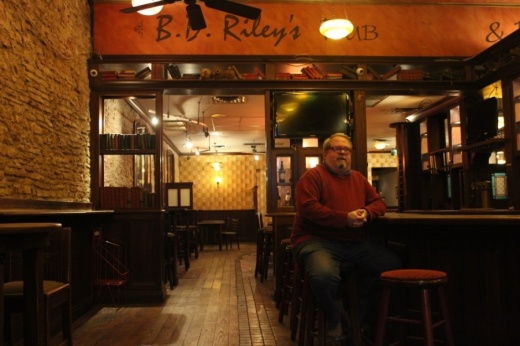

The pub opened in 2000 on East Sixth Street, just before the economic downturn of the dot-com bubble burst and struggled while tourism and travel came to a sudden halt following the 2001 terror attacks. Less than a decade later, the small Irish pub would make it to see the other end of the Great Recession. Citing the pandemic, the bar’s owners announced Aug. 27 that B.D. Riley’s Sixth Street location would permanently close; however, its second location in the Mueller development would remain open and has since thrived.

“In downtown, we depend on foot traffic and vehicle traffic driven primarily by visitors, hotel guests, conventioneers and locals who want to bar hop,” co-owner Steve Basile said. “There was no path that we could draw that was anywhere more optimistic than 10 or 12 months of financial loss before downtown began to see the things that made downtown what it was pre-pandemic.”

Convention-less. Festival-less. Tourism-less. In downtown Austin, the pandemic has taken the regular menu of revenue drivers off the table, and the public health risks now attached to large, in-person gatherings and out-of-town travel have placed a particular burden on small businesses in the city’s central business district bound by Lamar Boulevard, I-35, Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Lady Bird Lake.

The drain has made the math especially difficult for restaurants and bars, where bottom lines also depend on a now-dissipated office workforce, and smaller real estate footprints exacerbate the impact of social distancing rules. According to Community Impact Newspaper’s tracking of business closures, at least 10 locally owned restaurants and bars have permanently pulled out of downtown since August but, like B.D. Riley’s, have maintained business operations in other parts of the city. Their reasons signal a pessimism about the pace of recovery in the city’s center.

Downtown Austin has been changing rapidly for years, but those in the industry say the drain of tenured names such as B.D. Riley’s, Counter Café, Easy Tiger, Second Bar + Kitchen, Austin Java, P. Terry’s, Dai Due and Biderman’s Deli has left a sizable local hole that could be difficult to fill as development pressures increase and rents continue to climb.

Business owners who spoke with Community Impact Newspaper cited the pandemic as the main reason for closure; however, all listed contributing factors such as soaring property taxes, concerns about public safety and the rise in the visibility of people experiencing homelessness. Few local efforts are underway to ease the specific burden on these downtown businesses, and the timeline toward normalcy remains hazy. Difficulties of urban density

With the success of his shop in Northwest Hills, Zach Biderman, owner of Biderman’s Deli, saw an opening at Eighth and Brazos streets as a chance to capitalize on a reliably strong weekday lunch market. After opening in October 2018, the new location quickly became the top earner.

When the pandemic struck in March, much of his office clientele transitioned to working from home, and the ingredient that was once cause for success downtown suddenly turned to an insurmountable obstacle. With his customer base decimated and a curbside model logistically difficult with limited parking in the area, Biderman closed his doors in March and officially announced in September that they would not reopen. However, Biderman’s North Austin location has succeeded.

“I would need downtown to be at least at 75% of where things used to be for it to really make sense,” Biderman said. “At some level, I’m surprised any restaurants are down there right now.”

A mile west of Biderman’s downtown, Debbie Davis permanently closed Counter Cafe on North Lamar Boulevard, where it operated since 2007. Davis said the diner could not survive the combination of social distancing regulations and downtown rents. However, Davis said she is confident in her other two locations on East Sixth Street and on 29th Street.

“I could only have, like, four people in the building 6 feet apart. Really, are you going to sign another lease when you can’t seat the building?” Davis said. “I mean, it’s a little 700-square-foot building on a gold-mine piece of property in downtown Austin. We knew it wasn’t sustainable.”

Basile said space during a time of social distancing gave the Mueller location of B.D. Riley’s, which has a patio and openable floor-to-ceiling windows, an advantage.

“At 50% occupancy in Mueller, we’re running about 70% of our normal revenue. At 50% occupancy in downtown, we were doing about 20% of our pre-COVID revenue,” Basile said. “So, you have two very similar pubs, very similar concepts and very similar square footage. But one is in a residential neighborhood with a patio, and one isn’t in a residential neighborhood and without a patio. That’s where we did the hard math.”

Biderman also attributed his Northwest Hills success to different infrastructure and a more loyal, residential customer base. Co-owner of Austin Java, Tomas Fernandez, closed his location next to City Hall in August but kept open his location along Menchaca Road, which has a drive-thru, for similar reasons. Even after seven years, Fernandez said the loyal customer base came from office workers, not downtown residents.

Pete Clark, co-owner of Cafe Blue, has kept his locations open—one downtown and one in the Hill Country Galleria. He said his downtown business has been crippled but believes both locations will survive.

“Downtown is great when times are great, but it’s particularly bad when times are bad,” Clark said. “I believe that once people feel comfortable to move about the city ... there will be a real pent-up demand.”

Drafting a recovery

The Downtown Austin Alliance, a group of downtown stakeholders, launched a “roadmap to recovery” and convened a group of business stakeholders, city officials, consultants and experts to strategize a pandemic exit. They have lobbied the city for funding and piecemeal reforms, such as making it easier for businesses to get permits to expand onto sidewalks and parking lots.Michele Van Hyfte, DAA’s vice president of urban design, said the alliance is also researching how to better “curate” a more resilient downtown for the future.

“The smartest thing we can do is look at the best possible way to put businesses back into those vacancies. But what’s the right mix of businesses? And what would they need to be able to survive not only the good times but the bad times?” Van Hyfte said.

Fernandez said, if given the chance, he would not return to downtown.

“Unequivocally, 100%, I would never go back downtown and put in an Austin Java,” Fernandez said. The cafe closed its original location near House Park in 2017. “It’s just too expensive to be downtown. We’re not a home-run hitter that is killing it making millions of dollars. We’re surviving as a small business, and a downtown location just wouldn’t work for us.”

Biderman said he would come back to downtown but would want to work with the city to address the growing homelessness issues. Davis said she was unsure if Counter Cafe would return downtown but emphasized the city needed to do more for people to feel safe in the area. For Basile, it would be about numbers.

“Will we go back? Maybe if the right location appears at some point down the road, and the numbers and the projections make sense,” Basile said. “Sure, not ruling it out.”