By then, Austin was in the midst of its third catastrophic coronavirus surge. Hospitals in Austin’s 11-county trauma service region had treated more than 134,000 coronavirus patients, and Travis County was within a week of recording 1,000 deaths from the virus.

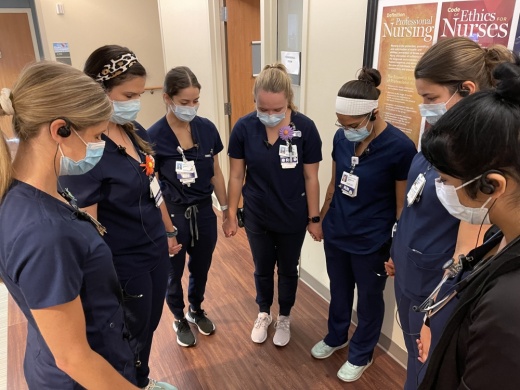

“[Our workers] honored those affected by COVID-19. ... For many, that includes family and friends,” Baylor Scott & White Health, St. David’s HealthCare and Ascension Seton said in a joint statement. “Health care workers have shown incredible courage and resiliency. Today was a time to honor their continued work.”

But after 18 months of pandemic conditions, the ranks of those workers were smaller—especially among nurses.

The three hospital systems said in July that a pre-existing nursing shortage had worsened as the delta variant sent patients in droves to the hospital. The surge has continued through September, and short staffing continues to restrict the capacity of already packed intensive care units.

According to Texas Workforce Solutions, there were 5,172 help wanted ads for registered nurses posted in the Capital Area in the second quarter of 2021. The open positions equal almost half of the 10,200 registered nurses who worked in the area in that time frame. Cindy Zolnierek, CEO of the Texas Nurses Association, said the nursing shortage is longstanding and complex with roots in compensation disputes and insufficient resources in nursing education programs—but 18 months of high-stress work has brought the crisis to a fever pitch.

“Frankly, I am very concerned about the nursing workforce,” Zolnierek told Community Impact Newspaper. “There are nurses who are going to weather it through this crisis, but then they’ll say, ‘I’m done.’ What that will mean—at the same time as we’re struggling bringing new nurses in for a number of reasons—is it’s going to be a very challenging time moving forward.”

Staving off burnout

Since July, the number of available, staffed ICU beds in Austin has fluctuated between zero and five, according to Austin Public Health. While hospitals may postpone some elective procedures when capacity is so limited, they do not begin turning away patients with necessary care needs as soon as ICU capacity reaches zero, Austin hospital systems representatives say. However, they may have to ask staff to take on more work, including tasks not normally in their job description.

“All three health care systems are sourcing staff using multiple resources, increasing shifts, paying critical staffing bonuses and redeploying non-nursing staff to assist with non-clinical tasks,” the hospitals told Community Impact Newspaper in a joint statement.

In these circumstances, nurses are made responsible for more patients, said Jenna Laine, a nurse practitioner and a professor for Austin Community College’s mobility nursing program, an accelerated program for students with some pre-existing nursing experience.

“Most places I’ve worked, an ICU nurse takes on one to two patients,” Laine said. “There might be places [now] that might be trying to have an ICU nurse work for three patients, and that’s just way too much, because we’re talking about patients that need to be checked on every five to 15 minutes.”

Many nurses are also being scheduled to work back-to-back shifts, often while caring for patients facing grim outcomes, Zolnierek said.

“Folks are just exhausted,” she said. “There comes a point where [COVID-19 patients’] chances of survival are very, very low, so nurses are seeing a very high incidence of death. And that makes the work very difficult, because in some ways, it feels hopeless.”

Competing for talent

As pandemic-related burnout causes many nurses to leave the field, those who remain have options. Many have accepted higher-paying offers from travel nursing agencies supplying staff to overburdened hospitals, Zolnierek and other experts said.

Selena Xie, a surgical ICU nurse for Dell Seton Medical Center and President of the Austin EMS Association, said the pandemic “decimated our ranks,” and estimated that around 50% of her colleagues who have resigned accepted jobs as travel nurses.

“Wherever COVID[-19] is hardest hit, they’re offering them really big bonuses to go and work there for like two months,” Xie said.

This summer and fall, Texas has been one of those hardest-hit areas. Gov. Greg Abbott announced Aug. 19 that he would contract with staffing agencies to deploy supplemental staff to hospitals across the state. To avoid Texas nurses leaving their current positions in favor of more lucrative traveling contracts—a phenomenon that was common earlier in the pandemic, Zolnierek said—Abbott required the state-funded supplemental staff to come from outside of Texas, as seen in job postings from state-contracted staffing agencies such as Krucial Staffing.

Nurses deployed to Texas with Krucial earn a base salary of $125 an hour, outstripping the median pay for RNs in the Austin-Round Rock area, which sits under $35 an hour, according to the Texas Workforce Commission.

Travel nursing positions in other states, including Florida, remain plentiful. In order to compete, all of Austin’s major hospital systems currently offer bonuses to new ICU nursing hires. However, to retain nurses in the long run, Xie said Austin employers need to match the pay scale present in other Texas cities: Dallas RNs make nearly $37 an hour, and Houston nurses make around $40 hourly.

“Even before the pandemic, we would have a lot of people leave for Houston or Dallas,” she said.

Education bottleneck

Also contributing to Austin’s nursing shortage is a lack of supply at the entry level. Local registered nursing programs have a waiting list of qualified applicants every year, but lack the space, faculty and resources to accommodate them, said Leigh Goldstein, a nursing professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

“I believe there are a lot of people who would go to nursing school if they had the opportunity to get in,” Goldstein told Community Impact Newspaper. “[It] really puts a chokehold on things if you don’t have enough faculty.”

As of 2019, only 1.2% of Texas nurses were qualified to teach, holding a doctoral-level degree in nursing. However, nurses in that pool often choose to work as a nurse practitioner—typically a better paying role, Zolnierek said.

Austin also has limited clinical space to share among nursing programs, Goldstein said, which in Travis County include Austin Community College, UT, Concordia University Texas and others. Over the past two decades, Texas has sought to increase the number of nurses in the state through its Nursing Shortage Reduction Program, which provides grants to nursing education programs to help boost enrollment and graduation rates. Since its inception the program has succeeded in growing the nursing workforce; the number of active RNs has grown by nearly 43% since 2010 from 176,251 to 251,253.

Yet supply remains below demand. Throughout Central Texas, the Texas Department of State Health Services projects 31,608 RN positions are needed in 2021, with 26,935 nurses available, a shortfall of 14.8%.

Graduates step up

For students graduating from nursing programs this year, pandemic conditions are an expected reality. Amarachi Amaikwu, a 2021 graduate of ACC’s RN program, will soon to begin work for St. David’s HealthCare in October. She began her program in August 2020 with COVID-19 in full swing, taking most classes online. She and her classmates called their experience “pandemic university.”

“I definitely empathize with those who have left the field,” Amaikwu said. “However, I’m excited to jump in and help where I can as the pandemic continues.”

Nursing faculty have also adjusted their instruction over the past year and a half to prepare students for the environment they will enter, Goldstein said. That includes teaching students how to handle personal protective equipment in high-risk situations as well as the importance of practicing self care to avoid burnout.

However, with hospitals still strapped for staff, one nursing student said she is bracing for exhaustion.

“I’ve kind of mentally prepared myself to know that I may have moments where I’m like, ‘This is really a lot. What am I going to do?’” said Camille Batts, a UT nursing student who will graduate in December. “Nothing’s really going to prepare us for truly going into the pandemic.”