About one month after they moved in, the river was noticeably filled with more green algae than it was when they first saw it. They assumed it was typical, she said.

“[The algae] progressively got worse and worse and worse to the point where you couldn’t go down to the river,” she said. “It was everywhere.”

In September, she learned of the wastewater treatment plant located upstream.

Northeast of US 183 and the river lies the Liberty Hill Wastewater Treatment Plant. The plant discharges its processed water into the South Fork of the San Gabriel River, and it holds a history of state water quality violations.

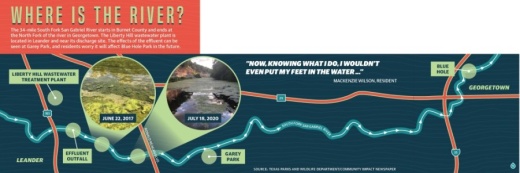

Photos provided to Community Impact Newspaper by residents who live near the river show a stark difference in the quality of the river on the east and west sides of the discharge site.

In June, the plant has earned seven complaints spanning 455 days from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Complaints include failure to prevent an unauthorized discharge, failure to properly collect effluent samples and failure to obtain authorization to discharge stormwater.

“Human health or the environment has been exposed to significant amounts of pollutants as a result of the violation,” state two of the TCEQ violations from 2018 and 2019.

Additionally, city-reported nutrient data shows heightened levels of nitrogen; E. coli; suspended solids, or particles that should be caught by filters; and phosphorus when compared to the maximum levels in the federal Clean Water Act, according to city and federal data on the river’s water.

The city of Liberty Hill plant has raised troubles for Leander and Georgetown residents following its violations of the state permit allowing discharge and federal regulations under the Clean Water Act. Though those affected live in Leander or Georgetown, the decision to resolve the plant issues comes down to the owner of the plant: Liberty Hill.

Dixon said she believes it should be preserved for future generations.

“I really have no idea what the ramifications are if it keeps up,” she said. “Already, it is not in a good space.”

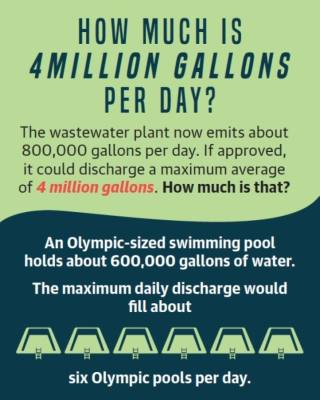

The plant, which discharges water east of US 183 into the South Fork San Gabriel River, is allowed to pump 1.2 million gallons per day, or MGD, of treated wastewater into the river. The city of Liberty Hill is now requesting a TCEQ permit renewal to allow the plant to discharge 4 million gallons per day—a 233% maximum increase to a river affecting river recreation, river appearance and property values, according to riverside residents. The plant currently processes about 800,000 gallons per day, per the city.

The permit is under review by the state commission. A public meeting was held Aug. 17 with formal comment and informal discussion periods. People against the permit submitted 203 comments, hearing requests and public meeting requests for contested case hearings, all to ask the commission to deny the renewal.

In a statement to Community Impact Newspaper, TCEQ said it considers compliance history when approving permit applications.

“Additionally, a permittee’s compliance record may result in additional permit requirements which are focused on improving permittee compliance,” it said.

In late 2019, Mackenzie Wilson moved into the same new-construction neighborhood as Dixon. Access to the river was a key selling point that the builders pushed, she said. A community trail runs along the river in their development.

“Now, knowing what I do, I wouldn’t even put my feet in the water right here,” Wilson said.

Wilson said she thinks the state’s reprimands have been insignificant.

“It’s been such small fines and tiny slaps on the wrist that it’s just not being taken very seriously,” she said.

Most recently, on June 10, the city of Liberty Hill was fined $91,651 for seven water quality violations. The city has declined to comment as of the time of publication. One violation includes a 2019 event in which 3,000 gallons of partially treated wastewater was released.

The city’s website says the partially treated solid was removed, and necessary components were replaced for alarms to work properly.

“Even this small amount of discharge—less than [1%] of the [water processed] the plant treats on a daily basis—is too much,” the city website states. “This situation provided an opportunity for city staff to evaluate protocols and improve processes to prevent this type of occurrence.”

Raymond Slade, a certified hydrologist of 49 years, said wastewater treatment plants pose huge human and environmental health threats across Texas. He calls it “an almost invisible threat” because most people cannot see the issue’s depth beyond the surface-level algae.

Within the water, flushed pharmaceuticals and industrial compounds are present because the treatment process does not fully remove them so when people fish or swim in the water, they can become sick without realizing the source. Slade said he would not swim in the Blue Hole Park, which is miles away from the Liberty Hill plant’s discharge site.

“Nobody knows how much nitrogen or phosphorous that most of the facilities are dumping in the streams,” he said.

Environmentally, the effluent’s high nutrient counts rapidly affect groundwater and aquifer sources like well water.

Slade said Texas has the most wastewater facilities in the country and is one of the least restrictive states in wastewater discharge. In his experience, TCEQ violations are far and few. The fines that Liberty Hill has received are very unusual, he said.

“They are very friendly to the industry,” Slade said.

‘They’re killing the river’

As a result of the river’s issues and its appearance, homeowners said, they fear property value dropping and unsellable properties. Some have already seen effects on their homes.

In July, Pam Sylvest lost her home’s sale after the buyers saw a sign in a neighbors’ yard warning of the river’s smell and concerns. The sign was meant to deter families from swimming in the river, Sylvest said, but it ultimately lost her the offer.

“That was 45 minutes before the close,” she said.

Sylvest said she has taken the loss as a sign she was not supposed to move, especially in a pandemic, where she is now glad to have the open land.

She said the river’s quality affected her property value, too, as she was paying property taxes on a home valued at $549,000. Because she could not sell it for $440,000, she said, she used her lost sale to reduce her home valuation with Williamson County.

She bought the home and 5-acre property 22 years ago as a place for her children and grandchildren to enjoy the river and rural land.

Now, Sylvest is surrendering to the situation; she said she begs for rain to wash the sludge out.

“It’s truly sad for my grandchildren. I worked all my life to be able to have this and give them a little piece of nature,” Sylvest said. “And what this has done to the most glorious part of those five acres is sad.”

Years ago, Sylvest said, her family would bring a cooler with drinks and a boombox to relax on the river.

Today, she said, her grandchildren suit up in waist-high boots to look at the sludge-filled river and scrub with soap and water afterward because they worry about what is in the water.

“Why is no one watching the river?” she asked. “This is our waterway. This is where our children play, and I’m sick about it.”

According to 2019 city projections, the number of Liberty Hill wastewater connections will increase by 197% from 2018 to 2028. About 11,000 of the 13,000 total customers will be residential out-of-city connections.

To allow for growth, the city has planned $75.9 million in wastewater projects in its 2019-28 capital improvement program, according to city documents. Projects include expansions of the South Fork plant and a proposed wastewater treatment plant on the North Fork San Gabriel River.

Georgetown resident LaWann Tull has lived on the river since 2007, when the river was only a “trickle.”

Her family would watch sunsets and eat meals outside, she said. Her church would perform baptisms in the San Gabriel River. She used to see fish and limestone in the water.

“They’re killing the river—flat killing the river,” she said.

To combat the city’s growth and the increase in wastewater processed, solutions, such as reuse of treated water, must be pushed, she said.

“We’re not after anything but clean water—safe water,” Tull said.

Clean Water Act

Stephanie Morris moved her family to the South Fork San Gabriel River river seven years ago.

“The last few years, it has just been extremely depressing,” she said. “Our life’s savings, our life’s work is invested in the property.”

Morris’ family prays for floods to wash out the river’s sludge and muck, she said. But those are just temporary before the river turns “nasty” again.

Morris began taking action to save the river—or what is left of it, she said—five years ago.

On Sept. 4, on behalf of Morris, Texas RioGrande Legal Aid gave the city of Liberty Hill a 60-day notice of intent to file a Clean Water Act lawsuit against the city of Liberty Hill “to halt significant, chronic, and ongoing violations of the Clean Water Act” and “to seek penalties against the City for past and ongoing illegal discharges from the City’s wastewater treatment plant,” the notice letter said.

The lawsuit seeks the enforcement of 3,108 discharge permit violations.

Under the Clean Water Act, penalties total $55,800 per violation per day paid to the federal government.

The CWA, which is overseen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, will bring Liberty Hill’s violations to a federal court and seek penalties, said Amy Johnson, an attorney representing Morris. The goals are for the city to comply with its wastewater permit and to return the river to its native, pristine quality, she said.

Johnson said that although the steam is outside city limits, they hope the city cares about the local stream and the environment.

“And if they do, then the question is, ‘Why would they want to put more and more wastewater into this stream when, even at this little bitty amount, they’re already doing damage?” Johnson said.

If the parties do not settle, outcomes of the lawsuit could include a stricter, more protective permit for the stream, permit violations or a failed renewal, Johnson said.

According to city worksheets and EPA data, as well as the lawsuit, the plant has exceeded phosphorous permit limits for 994 days, ammonia nitrogen permit limits for 1,070 days, total suspended solids permit limits for 321 days, carbonaceous biochemical oxygen demand permit limits for 66 days and E. coli permit limits for 20 days.

Morris said the lawsuit felt like the only option left and said she believes there should be “reverse 911” communication from the plant when the E. coli level is high. After several years of no alerts, she now receives notifications a few days after a violation, which is too late, she said.

She hopes that the city would work with future developments to create a reuse program for the water. Reuse wastewater could be for irrigation or sent to water treatment plants. If costs are high to implement reuse, Morris said the decision should be left up to the customers.

She said the few TCEQ violations don’t always give the big picture.

“Even during the time periods that there haven’t been any violations for months, the condition of the river—at and below that plant—is not just unsatisfactory,” she said. “It is grotesque and unusable.”