Saunders, who has been with LISD for 15 years, is the team lead for CNS at the school and, pre-pandemic, ran a team of 16. But while she and other members of her crew were out in January, the team was down to the bare minimum.

“I was out for three weeks with COVID[-19] and pneumonia and, one day, there were only two of my staff here—that’s it,” Saunders said. “We had to pull people from other schools or other parts of the district, and we brought them in to feed the kids. You can’t do it with two people. I mean, they’re strong, but you can’t do that.”

And it was not just Vista Ridge that was hit hard.

As the omicron variant of the coronavirus reached its peak in January, LISD reached a tipping point.

“That’s really when we saw it get to a point where some of our cafeterias were operating at 50% staff capacity,” said John West, LISD’s senior director of support services and staff and employee relations. “When we, as a district, start looking at not being able to serve food or clean the cafeteria or fill in for substitute teachers, that’s when we reached out to our volunteers and our community and our staff.”

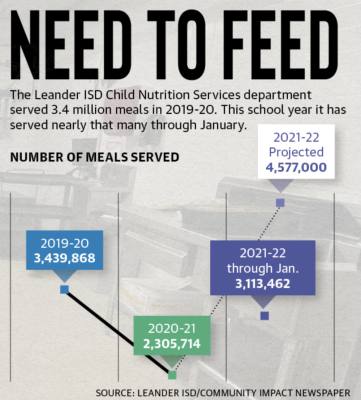

During the 2019-20 school year, the LISD nutrition department served 3.4 million meals for breakfast and lunch, but that number dropped to 2.3 million in 2020-21 when many students remained virtual. In the current school year, however, the district is on pace for its highest numbers, having already served 3.1 million meals through January.

“When you take the staffing issue on top of [the fact that] we’re serving more meals now than we ever have, that’s incredible,” West said. “You’re talking about eight people serving 1,500 kids.”

School districts nationwide have long utilized volunteers as crossing guards or to help teachers make copies or prep arts and crafts. But LISD was now thinking about using them more creatively.

Year two of free meals

For the team at Vista Ridge and the others around the district, the 2021-22 school year also brought with it a new challenge: free meals.

In October 2020, LISD announced that through a waiver with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, every child in the district would be eligible for one free meal per day for breakfast or lunch. But with many students still learning virtually, the total served was still well short of the previous year’s efforts.

“I used to run the kitchen with 16 people, and when we came back [in 2020] I think I had nine people, but we would loan people to other schools every day, so I was down to four or five,” Saunders said. “But we also went from serving 2,200 total meals ... to like 300 or 400 a day last year.”

But when the USDA extended the free meal waiver through the 2021-22 school year, it meant that Saunders’ team once again was responsible for serving close to its pre-pandemic numbers but with half of the staff.

Districtwide, LISD averaged nearly 19,000 daily meals in the months leading up to the pandemic in March 2020. Through January of the 2021-22 school year, that daily number is 28,494, an increase of about 50%, according to LISD.

The cafeteria at Vista Ridge is laid out like a mall food court complete with colorful signs to denote different offerings such as Luigi’s Eatery or Ballpark Classics. These stations formerly had trays of carefully laid out options to entice students. Saunders and her team have streamlined the work to focus on ensuring every student who wants a hot and fresh meal gets one.

Some of the efficiencies are subtle and built around limiting trips to restock in the midst of a lunch rush or extending shifts to prep for the following day’s service. Others are more obvious.

“It used to be the kids would come through and tap in their [account] code, you’d ring up their food and they’d move on, but we don’t have time for that. So we stand by the doors and have tally sheets,” Saunders said. “They come through, get their meal, and we do a tally and at the end of the day, I ring it all in.”

Volunteers chip in

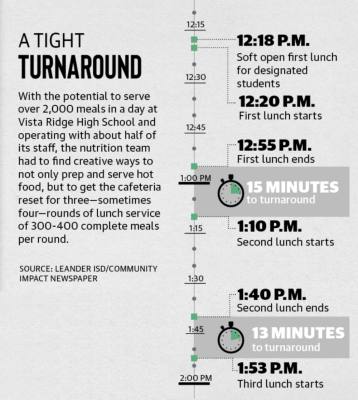

Technically, the turnaround time between the normal three lunches at Vista Ridge is between 13-15 minutes to bus several dozen tables, change out the trash cans and generally reset the large room. But as students linger, finish eating and head off to their next class, that window quickly shrinks.

“The thing that has been the biggest help for us is when [volunteers] come and they just take care of the tables and the trash,” Saunders said. “It’s more like seven minutes between all three lunches—seven minutes to change 14 trash bags, take them out and to [clean] all those tables. When I have five or six people working, it just can’t be done.”

That gap has been filled at Vista Ridge by parent volunteers as well as the school’s own administrative staff, including Principal Paul Johnson, a move that allows the CNS team to remain in the kitchen and prepare for the next wave of students.

At Winkley Elementary School in Leander, Kat James has taken the opportunity to be involved at her kindergartener’s school and, in addition to supporting teachers by taking “menial tasks off their plate,” has enjoyed time in the cafeteria.

“I wanted to help out,” James said. “I know the staffing is low, but I wanted to be involved in the school and school district. At lunch, we help the smaller kids open milks or their fruit gummies. If they spill something, we clean it up and wipe down the tables. I don’t think the cafeteria staff could do it without volunteers.”

In addition to parental volunteers and on-site staff pitching in, employees from LISD’s office in Leander have also taken time out of their day to help out. The district would send out a virtual list allowing them to fill in at the campuses with the greatest need on a given day.

“It felt like every day I saw that Google Sheet fill up by willing volunteers, people who were doing their jobs on top of going and serving,” said LISD’s Community Relations Coordinator Rachel Acosta, who has volunteered at several of the district’s campuses. “It was a wonderful experience to be able to not only do it but to see other people doing it.”