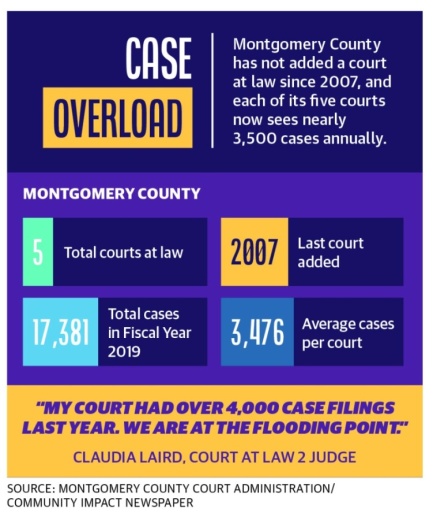

The proposal for adding two courts was originally presented to the county commissioners Jan. 12. At the meeting, Court Administration Director Chad Peace said case counts and the county population have increased by 26.2% and 32.4%, respectively, since the last court at law was established in 2007.

Courts at law hear cases including issues of probate, mental health, juvenile and family issues, according to information from the Texas Judicial Branch.

However, while the resolution approved by the commissioners Jan. 26 expresses support for one court, it will not become functional until September at the earliest and, depending on whether a judge is appointed, may not be in use until 2023 at the latest. If a judge is not appointed, an election could be held in November 2022 if both a Republican and a Democrat choose to run in that year’s primary election. The winner would take office Jan. 1, 2023, according to court officials.

Judge Claudia Laird, who represents Montgomery County Court at Law 2, said her court is “at the flooding point.” In 2020, her court received over 4,000 new case filings.

“Every month, every week, I am searching the calendar to find time,” Laird said. “There are things that have to be done, and there are not enough hours in the day to do them.”

Laird said the need for a new court has been discussed for the better part of three years, but a new court can only be created during a session of the Texas Legislature. Due to this restriction, discussions among the Montgomery County Board of Judges began in earnest around three months ago.

Among the concerns the commissioners have moving forward are the general costs of adding a new court, which during the presentation were cited between $500,000 and $1 million, and where additional courts will be established, as the current courthouse is nearly out of space.

A matter of need

Peace said Montgomery County’s average caseload per court is higher than most similarly sized counties. During his presentation, Peace said the Montgomery County courts average around 3,476 cases per court per year among five courts at law, compared to Denton County, which has a total of eight courts at law and averages 2,283 cases per court per year.

Montgomery County’s average case count per year is around 1,200 to 1,400 cases higher than Denton County, Peace said. The originally proposed two courts would have lowered the average case count from 3,476 to an estimated 2,483 annually and, Peace believes, would have better prepared the county for continued growth.

The commissioners made their decision to approve the court after taking two weeks between Commissioners Court sessions to work with the board of judges to understand its needs.

Laird added if the request to have one of the courts had not been fulfilled, by the time of the next legislative session in 2023 her office would have had to ask for four or five courts instead.

The request for a new court has been sent to state Rep. Will Metcalf, R-Conroe, to introduce during the session. Metcalf could not be reached for comment as of press time.

Effects of the caseloads

Judges are not the only ones feeling the effects of high case counts per court. Penny Wilson, the chief operating officer of Montgomery County nonprofit Yes to Youth, said families involved with the courts at law can feel like the system does not care about their issues.

“It just can feel like there’s not a sense of urgency, so they can feel like, ‘OK, I’m just a number on a docket. My issue isn’t really being looked at, or they’re not concerned about how this is affecting our family because it was considered like business as usual for the judges and attorneys,’” Wilson said. “Things like that just create a little bit of animosity between the justice system and the families going through the court system when they feel like their concerns aren’t being really paid attention to and taken seriously.”

Yes to Youth, formerly Montgomery County Youth Services, offers counseling and shelter for teens. It is among the area nonprofits associated with helping families involved in the court at law system.

“We receive a grant called the Victim of Crime Act, and we help families and kids who have been victims of crime in our counseling program through that stream of funding,” Wilson said. “While we do not go into the court and advocate for the kids and serve in that capacity, we do have families that are going through the court system whether they have had a domestic abuse case and they are needing to file a restraining order or go through custody battles or things like that.”

Wilson added the main complaint Yes to Youth hears is about the backlog of cases in the courts.

“That just kind of tends to be an impact because it is really hard on a family that is going through a situation to get to that healing stage when things feel unresolved or there is no closure on a case,” Wilson said. “Sometimes there will be a lot of activity in a case, and then they will not hear anything for a while. ... And that can be very frustrating and unsettling for families as well when it just feels like things are just dragging on and on.”

Moving forward, Wilson said she would like to see better transparency from the court system as a whole on its workflow and timelines.

Laird said as a judge, she is trying to find time on a daily basis to make room for hearings, reaching out to judges for help or seeking a visiting judge.

Cost and space concerns

Two of the main questions brought forth by Montgomery County commissioners were the costs associated with the new court, which will have to be funded by fiscal year 2023, as well as where the court will be held.

Information from Montgomery County Budget Officer Amanda Carter indicates the new court might cost around $725,000 to create, although a worst-case scenario was provided, which would cost about $850,000. The costs associated with the court largely come in the form of salaries for the judge, court administrator, court coordinator, and county and district clerks, she said.

Funding for the court will need to be ready by September at the earliest if the commissioners choose to appoint a judge to fill the created seat, she said.

Another concern county officials spoke about is where the new court will go. For the time being, Laird said the old Child Protective Services court, which acts as an overflow court and where the Commissioners Court used to meet, has enough space to fit the new court.

During the Jan. 12 meeting, Precinct 3 Commissioner James Noack said he was not inclined to build a one- or two-story building behind the current courthouse.

“I think we would need to build another building just like [the courthouse] and shuffle a lot of things around to create more and better courtroom space and more secure courtroom space,” Noack said. “It is something we are going to need to consider.”

Laird said she believes the discussion about where to put future courts needs to happen, as the county’s court system will need to keep up with a growing population.

“I think this lets itself to a larger conversation we have been having with [the county] about the inadequacies of the courthouse complex for growth, space and security,” Laird said.

In a separate phone interview, Laird said the board of judges will need to determine moving forward what kind of cases need to be put into the court.

“Judge [Tracy] Gilbert, the district court administrative judge, was in the presentation, and he indicated during the hearing that two years from now, the commissioners should expect a request for a new district court,” Laird said.

Laird added she thinks the addition of the new court was a responsible decision by the Commissioners Court.

“Our mental health cases are skyrocketing,” she said. “They are multiplying exponentially. That is one of the places we need relief, and I think they are doing what is in the best interest of the people of the county to make sure there are judges to hear these cases in a timely manner.”