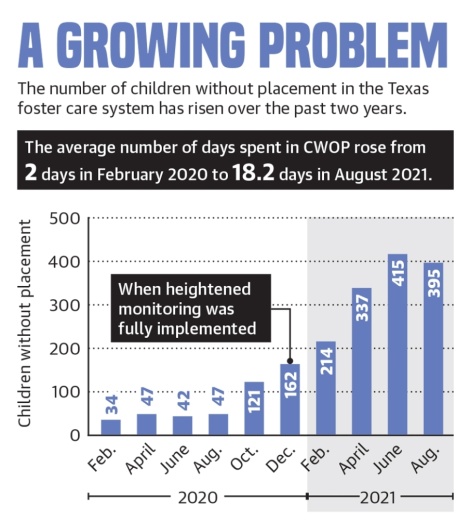

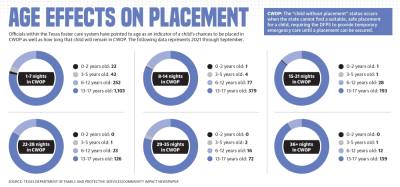

According to DFPS officials, individuals in the state’s foster care system receive a “child without placement” designation, or CWOP, when the state cannot find a suitable placement for that child, requiring the DFPS to provide temporary emergency care until a placement can be secured.

Over the last two years, the state has increasingly relied on placing children in unlicensed placements—often motels or office buildings—overseen by caseworkers. In October 2019, 32 children were in such placements statewide, according to DFPS data. In August 2021, that number had risen to 395 children.

Lisa Johnson, executive director of Entrusted Houston, a Cypress-based nonprofit that assists the DFPS in its goal of family reunification, said the nonprofit has been working tirelessly to address the issue.

“We are definitely trying to handle the crisis that is the CWOP,” Johnson said. “The caseworkers, the supervisors—they’re trying to do everything they possibly can.”

In Harris County, CWOP numbers have also trended upward over the last year, although the total number per month has remained lower than statewide averages. In September 2020, two of the 1,635 children receiving DFPS services were placed in CWOP. By September of this year, eight of the 1,415 children receiving services had been placed in CWOP.

DFPS officials and representatives from other entities within the state’s foster care system have attributed the increase to challenges associated with the ongoing coronavirus pandemic as well as caseworker turnover and recently enforced regulations that were mandated after the state lost a federal lawsuit in 2015.

Extenuating circumstances

In an August CWOP report, DFPS officials said the number of children in CWOP had risen in part because of heightened monitoring regulations mandated after U.S. District Judge Janis Graham Jack ruled in 2015 that foster children in Texas “almost uniformly leave state custody more damaged than when they entered.”

According to the report, heightened monitoring is implemented when certain entities within the foster care system have had a high enough rate of standard and contract violations to deem them an unsafe and unsuitable placement.

Entities placed under heightened monitoring are given a remedial plan by court monitors to address deficiencies and are subject to weekly unannounced visits to ensure compliance. Operations that fail to address the issues within a year can have their licenses revoked, placements suspended or contracts terminated, or can incur fines.

Since January 2020, 21 general residential operations—facilities housing 13 or more children—have been shut down or had their licenses revoked statewide, resulting in the loss of roughly 1,200 beds, according to a court monitor update issued in September. Moreover, several entities facing heightened monitoring voluntarily closed during that time, resulting in the additional loss of 375 beds and 157 verified foster homes.

Christine Weber, chief financial officer of Circle of Living Hope, a Houston-based child placement agency, said while she supports the new regulations, heightened monitoring has contributed to the closure of several placement options the agency had previously worked with.

“We have closed quite a few homes in the last year—homes that have sparked a lot of investigations,” she said. “It could be homes where maybe there weren’t any deficiencies [found] or there was nothing proven, but if there are a lot of [investigations], the state looks at it like, ‘Where there’s smoke, there may be fire.’”

According to Rebecca Mercer, regional director of statewide adoption agency Lonestar Social Services, heightened monitoring has also led to some foster parents removing themselves from the system altogether.

“It’s forced us to enforce stricter rules on our foster parents, and they have definitely felt the heat from that, which, in turn, turns foster parents away because it’s just too stressful,” she said.

Still, Mercer said she understood why the restrictions were needed.

“We’re trying to weed out those parents who may not have the best interests for the child because there are some out there,” Mercer said.

Additionally, Mercer said difficulties arising from the pandemic have made finding suitable placements for children more difficult.

“We’ve had a lot of foster parents that will come to us and say, ‘Until COVID[-19] is over, we’re not interested in taking placements anymore because it’s just too much,’” she said.

Searching for solutions

In a September CWOP report, DFPS Commissioner Jaime Masters said many providers have cited heightened monitoring as a reason for declining a placement, although she noted that did not indicate the department’s disapproval of the mandate. Masters said caseworker turnover has also contributed to the growing CWOP numbers.

Between February and July 2021, the DFPS hired 319 conservatorship caseworkers. In that same time period, 309 caseworkers terminated their employment. According to caseworker exit surveys submitted in 2021, 86% cited work-related stress as a reason for terminating their employment, up from 40% in 2020.

Despite additional staff members, the average number of hours per week each employee spent supervising children in CWOP increased from 22.5 hours in December 2020 to 35.7 hours in July 2021, according to the September CWOP report.

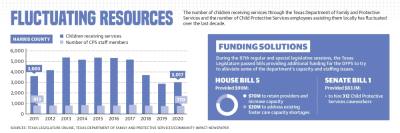

In Harris County, the number of children receiving DFPS services rose by 141 from 2019 to 2020, while at the same time the number of Child Protective Services staff members fell by 14, according to DFPS data.

In September, the Texas Legislature funded $83.1 million in Senate Bill 1 to hire 312 caseworkers, according to the DFPS’ September report. House Bill 5 allotted an additional $90 million to the DFPS, which will be used to retain providers and increase capacity to serve foster youth.

Spring resident Jeremy Galvan, who was employed as a caseworker for Circle of Living Hope from January 2020 to January 2021, spent six years in the state’s foster care system before aging out in 2014. He said he sometimes found it difficult to justify the trauma and stress he endured as a caseworker with the wage he was paid.

“I wouldn’t have to take home these internalized problems,” Galvan said. “I’m restraining a child who was sexually abused, and that messes me up as a human being just as much as that messes [the child] up as a human being. A lot of these things aren’t factored into the cost-benefit analysis when we’re trying to implement these policies at a macro scale, and while I agree [with heightened monitoring] wholeheartedly, there just aren’t enough resources.”

In October, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott approved the creation of a new expert panel to analyze the rising number of foster care children in CWOP. The three-person panel will issue recommendations to the governor’s office by mid-December.

Chandler France and Danica Lloyd contributed to this report.