Kelsea Heiman, an emergency room nurse at Houston Methodist Clear Lake Hospital, said nurses have felt a lot of extra weight on their shoulders while treating patients as COVID-19 guidelines continue to evolve. This has led to a sense of exhaustion for the nurses putting aside their own fears to provide patient care, she said.

“COVID[-19] has caused a lot of burnout,” she said. “People are starting to evaluate [their] work-life balance.”

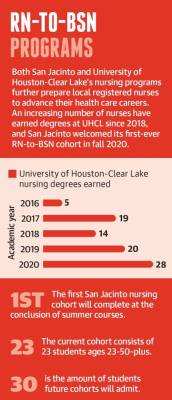

Educators at the University of Houston-Clear Lake and San Jacinto College also described a change in classrooms during the pandemic as both schools trained registered nurses in their RN-to-BSN programs. Working RNs can earn a bachelor’s degree in nursing at both universities, so UHCL and San Jacinto students have been coping with the realities of COVID-19 in the field while doing coursework.

These realities have led to the exacerbation of an already-present nursing shortage across the Texas Gulf Coast region, which includes Houston, local and regional experts said.

The Texas Department of State Health Services projects the Gulf Coast will have a deficit of 21,400 registered nurses by 2032 as the growing demand continues to outweigh supply. Though the region’s supply of registered nurses has grown 45% in the last decade, according to the state health department, experts said that growth is not enough to keep up with the population.

“The nursing workforce is just being stretched, and with that you lose quality,” Heiman said, describing the consequences of an overworked nurse caring for many critically ill patients and simultaneously keeping families informed of their conditions. “Who wants to be cared for by a bitter, cranky nurse?” Changing educational landscapes

Local educators are refining their programs to account for the changing needs of today’s patients, nurses and nursing faculty.

The first-ever cohort of BSN students started at San Jacinto in fall 2020 and will graduate at the end of the summer 2021 session. These students were applying for and completing the program during a pandemic, which necessitated making time in the classroom to properly address the effects of COVID-19 on student and staff lives, said Rhonda Bell, San Jacinto's dean of health and natural sciences.

Some faculty decided to retire earlier, leaving the remaining instructors susceptible to increased burnout, Bell said. Although she hopes resuming in-person education will re-energize faculty and remind them why they chose education over practice, she expects nursing faculty shortages to be magnified by COVID-19-related fatigue.

UHCL’s RN-to-BSN program has awarded nearly 80 nursing bachelor’s degrees in the last five academic years, per university data. Program classes are all taught at the Pearland campus, university officials said; UHCL opened a three-story, $24.6 million facility in 2019 to allow for expansion of its health care degree programs.

RN-to-BSN program director Karen Alexander echoed Bell’s sentiment that the effects of COVID-19 are felt by nursing instructors.

“We, too, are going through something, living the experience through the eyes of the students,” she said.

Alexander teaches her students to accept, adapt and overcome while working as nurses and facing adversity. Many students have had field work opportunities vanish or become otherwise complicated due to COVID-19 regulations, she said.

These students are experiencing complications around finishing their coursework while already being under pressure from the competitiveness of their programs. The state health department reported 54% of qualified applicants were not granted admission to one of the region’s 27 pre-licensure registered nurse education programs in 2019 due to a limited number of seats available. Still, watching nurses work through a public health crisis seems to have motivated the next generation to seek a career in health care, Bell said.

“I think that they have been inspired, watching what nurses have been doing for this past year and a half,” she said. “It has inspired them to stay focused and get this BSN because they see the potential growth in their careers as they do that.”

Addressing pay equity

Remedying the nursing shortage involves caring for the social and emotional needs of current students, but also involves furthering nurses’ education past a BSN and providing for better educator pay, experts said.

Nurses experiencing burnout at the patient level of care may choose to take their career in another direction by going into nursing administration, Alexander said. UHCL’s course offerings focus specifically on leadership and management, aiming to help working nurses sharpen the tools they already have and prepare for this career shift.

Alexander said 98% of UHCL’s program graduates go on to complete graduate and doctoral degrees, which are necessary qualifications to be a nursing educator. However, investing time, money and effort into nursing school at any level is grueling, said Heiman, who has been a nurse for seven years.

“Life is expensive,” Heiman said. “The money is just not there.”

Nurses with doctoral degrees working in administration or leadership positions can earn significantly more than a nursing educator makes, Alexander said, which makes rectifying the shortage of educators an uphill battle.

“That’s a big hindrance as to why we have a nursing shortage,” Alexander said. “You need to find those who are dedicated to [nursing education] because they love it, not because of the money.”

Nursing administrators in Houston can make, on average, $20,000 more per year than their nursing faculty colleagues, according to data from ZipRecruiter and Payscale.com. The average annual pay for a Houston nursing administrator is about $89,000, where nursing faculty make an average of about $68,000 annually.

Nursing faculty turnover rate for Gulf Coast-area programs in 2019 was approximately 13%, and the faculty vacancy rate was 6.5%. Faculty pay equity remains an issue when it comes to addressing the shortage, said Dr. Renae Schumann, the former dean of Houston Baptist University’s School of Nursing and Allied Health who now serves as District 9 president of the Texas Nurses Association.

“We absolutely need more faculty, which means that the schools have to pay the faculty something that they consider desirable enough to leave the hospital,” she said. Aging populations and telehealth

For the local nurses choosing to enter or remain in the field, they are caring for more senior patients while dealing with an aging workforce and grappling with how to employ telehealth.

About one in four Gulf Coast nurses are over age 55. These nurses are treating an aging population: 10%-14% of Pearland and Friendswood residents are age 65 and older, according to recent U.S. census data. As telehealth increases in prevalence, screens and remote options present new challenges for nurses, nursing educators and patients.

San Jac officials are closely examining industry trends as they relate to treating patients remotely, Bell said. Students need to learn how to handle scenarios unique to telehealth as it continues to increase in prevalence, which means educators must be responsive to how the technology could change standards and practices, Bell said.

Telecommunications can make the process of treating especially elderly patients more difficult, Heiman said, as the patients attempt to navigate the new technology and advocate for themselves at the same time. Use of telehealth involves patients having consistent access to the technology needed for remote medical care, which is also not always possible, Heiman said.

The logistical difficulties leave nurses wondering if anything was lost in translation or otherwise unwittingly glossed over, she said.

“I think telehealth is going to change things a lot, and I don’t know if it’s for the better,” Heiman said. The median turnover rate in 2019 for registered nurses in the Gulf Coast region was 17.5% in hospitals, but much higher in long-term care facilities at 50%. Local long-term care nurses during the pandemic dealt with fear of infection from residents and anxiety around bringing COVID-19 home to their families, said Courtney Robinson, director of nursing at Friendship Haven Healthcare and Rehabilitation Center in Friendswood.

As the population ages, people live longer and more nurses are required for their care, which contributes to the nursing shortage as well, Robinson said.

“We’re trying to do the best we can to keep our staff here and make them feel like this is their home,” she said. “We choose every day to take care of other people’s family members, ... and to some residents, we are their only family. Those staff who make that decision to show up to work every day are heroes.”

Haley Morrison contributed to this report.