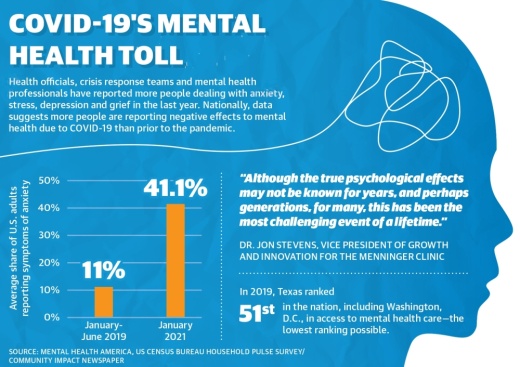

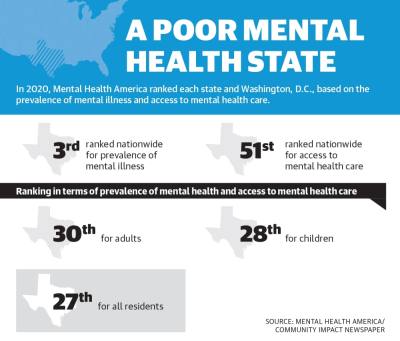

In 2020, Mental Health America ranked each state and Washington, D.C., based on the prevalence of mental illness and access to mental health care. Although Texas ranked 27th overall and was third in terms of prevalence of mental illness, the state ranked 51st for access to care.

Local experts said access to mental health care has been an issue in Texas since long before the pandemic. In 2017, Mental Illness Policy Org. reported the state allocated 1.2% of its total state expenditures to mental illness; this compares with states on the higher end of spending, such as Arizona, Pennsylvania and Maine, which allocated 4.8%-5.6% of their expenditures to mental illness.

“COVID-19 has challenged and changed mental health services, [and] unfortunately the mental health care system[s] in Houston and Texas proper were already inferior to many other states prior to the pandemic,” said Dr. Jon Stevens, vice president of growth and innovation for The Menninger Clinic, a Houston-based psychiatric facility. “Although the true psychological effects may not be known for years and perhaps generations, for many, this has been the most challenging event of a lifetime.”

As a result, Lake Houston-area mental health care providers, including The Harris Center for Mental Health and Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, Tri-County Behavioral Healthcare, and local school districts are struggling to keep up with an increased demand for mental health services across the board.

Breaking point

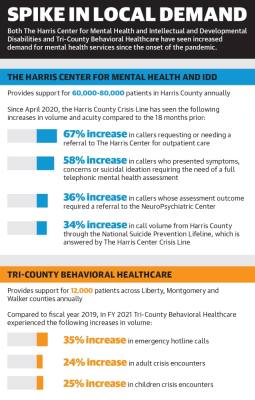

The Harris Center for Mental Health and IDD supports about 60,000-80,000 primarily underinsured or uninsured patients annually with everything from outpatient services to crisis intervention. Over the past 18 months, officials said they have experienced a significant increase in the demand for services.

According to data from The Harris Center, since April 2020, The Harris Center crisis line has experienced a 58% increase in callers who presented symptoms, concerns or suicidal ideation requiring a telephonic mental health assessment as well as a 34% increase in the call volume from Harris County residents through the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, which is answered by The Harris Center crisis line.

According to Dr. Luming Li—who joined The Harris Center as its chief medical officer in early August—prolonged isolation, economic challenges and delaying seeking treatment due to COVID-19 concerns have all played a factor in the spike in demand.

“We’ve seen some increases in acuity in the individuals that are being served, and one can surmise that it’s because maybe they didn’t seek care early enough or they waited for a while until their condition got significantly worse, so they’re coming in at a worse state than what we were seeing pre-pandemic,” Li said.

Similarly, Evan Roberson, executive director of Tri-County Behavioral Healthcare, said the certified community behavioral health clinic provided inpatient and outpatient mental health services to roughly 12,000 residents of Liberty, Montgomery and Walker counties over the past year.

“We’re up about 20%-25% across the board in terms of crisis services, routine intake, kids services and intellectual disability services,” Roberson said. “We’ve always had a high demand for our services because there’s high growth in our area, but one of the things we’ve noticed [since the onset of the pandemic] is a larger percentage of people showing up in crisis that have never sought [mental health] services before.”

In New Caney ISD, Loree Munro, the school district’s executive director of instructional programs, said the district has seen an increased demand for mental health services from both students and staff, with anxiety and depression being the top concerns.

“In our student population, we’ve seen a rise in suicide outcry, which is not a reflection of students who would make an attempt; rather, that is truly a reflection of students who had made some kind of outcry to self-harm,” Munro said. “Our district also partners with Life Assistance Program, which provides some behavioral and mental health services, and we’ve seen an increase in teachers seeking that information as well.”

Combined with limited funding, resources and increasingly burnt-out staffs, Li and Roberson said meeting the increased demand for mental health services over the past 18 months has required both entities to get creative.

Meeting needs

Like many health care providers, The Harris Center and Tri-County both relied heavily on technology throughout the pandemic. At The Harris Center, Li said telehealth has enabled many patients to seek treatment from the safety of their homes, although it does not come without challenges.

“People are sharing some concerns about coming to the clinic, so they’ve been really happy being able to use telehealth to receive services. But with telehealth, you’re not able to provide lab work or do physical exams, so that’s a concern,” Li said.

Similarly, while Roberson said Tri-County has also implemented telehealth and switched its intake protocol from a walk-in system to a call-in screening system, technology-based treatment is not an option for some of the entity’s more rural and lower-income areas, where many residents either cannot afford or do not have access to a reliable cell phone or internet service.

In addition to telehealth, each entity has implemented a slate of new programs and expanded offerings over the past 18 months.

According to Director of Communications Karen Boren, The Harris Center received roughly $15.9 million in COVID-19-related state and federal funding throughout fiscal years 2020 and 2021, which the entity used to establish a COVID-19 mental health support line, among other investments.

“This was a direct response to COVID-19 just because we saw an influx in mental health-related crisis calls to our crisis line,” Boren said.

In August, the Montgomery County Commissioners Court allocated $6 million of the funding it received from the American Rescue Plan Act to Tri-County, through which Roberson said Tri-County will open a new mental health facility for children in East Montgomery County by March. Roberson is in negotiations for a building in the Porter area.

“We’ll have our full-service array for kids in Porter once we’re there, so we’ll have psychiatry, therapy, crisis intervention and intake as well as all of our casework, case management and skills training,” Roberson said.

Additionally, both Tri-County and The Harris Center are using funds to help stabilize their respective workforces by bolstering staff pay and implementing incentives; Li and Roberson said the pandemic has taken its toll on the mental health of providers as well, leading to burnout and retention challenges.

“We’re struggling; I have 100 positions open right now,” Roberson said.

In Humble ISD, the district used federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds to add three student wellness counselors and one mental health officer to its staff this school year, as well as an additional counselor to the Homeless Education Office, which was funded through a Texas Education for Homeless Children and Youth grant. HISD is also conducting a district counseling survey from Oct. 13-27, the results of which will be analyzed to determine future needs.

While NCISD already had partnerships in place with Tri-County and Yes to Youth, since the pandemic, the district has also established partnerships with The Menninger Clinic and the Memorial Hermann Northeast Mental Health Crisis Clinic.

The district also received a one-year $50,000 matching grant from Mental Health America and used ESSER funds to expand social-emotional learning curriculum districtwide. Prior to the pandemic in fall 2019, NCISD was piloting social-emotional learning curriculum at five campuses.

Additionally, NCISD expanded its crisis team and added a crisis wraparound counselor—a social worker who is able to follow up with a student’s caregiver outside of school to ensure they have access to the necessary mental health resources.

“The school systems are being called upon to address the whole child—not just the cognitive abilities of the child,” Munro said. “Mental health and social-emotional learning are integral to the academic success of the students.”