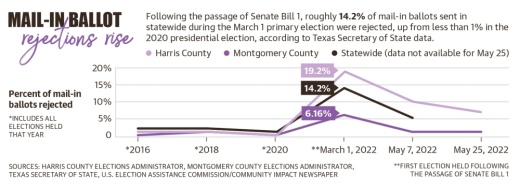

Statewide, a total of 24,636 mail-in ballots were rejected in the March 1 primary election—roughly 14.2% of all mail-in ballots submitted, according to Texas Secretary of State data.

According to a 2021 U.S. Election Assistance Commission report, Texas rejected roughly 8,000, or 0.08%, of the nearly 1 million mail-in ballots cast in the 2020 presidential election.

The new regulations surrounding mail-in voting are one of many laws included in SB 1, a voting reform bill that was approved by the Texas Legislature in September.

According to Sam Taylor, a spokesperson for Texas Secretary of State John Scott, the addition of reconciliation reports—which require counties to compare the number of voters who cast valid ballots with the number of votes counted by their tabulation system—has added a new layer of transparency.

“The reconciliation form that was added in SB 1 has been the biggest help for our office in terms of hunting down any issues that we see in the reporting of results,” Taylor said.

Since 2015, the state has successfully prosecuted 155 individuals for election fraud offenses, according to the Texas Attorney General’s Office. While the new voting-by-mail regulations were approved to reduce the potential for fraudulent voting, local election officials and policy experts said the regulations have added hurdles for individuals who vote by mail.

Among the officials who encountered issues with the new mail-in ballot regulations was Harris County Elections Administrator Isabel Longoria, who resigned from her position in April effective July 1 following challenges with mail-in ballots during the March 3 primary. As the county works to adapt to SB 1, the Harris County Election Commission has tasked an executive search firm to fill Longoria’s position by June 30 to help lead county elections ahead of the November general election.

Mail-in ballot rejections

To be eligible to vote by mail in Texas, state law dictates an individual must be 65 years old or older; sick or disabled; out of the country; expected to give birth; or confined to jail but otherwise eligible to vote.

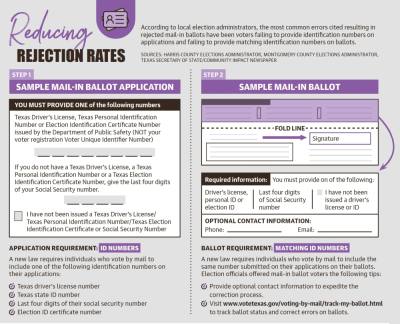

Under SB 1, voters are required to provide a partial Social Security number or driver’s license number on their mail-in ballot applications to receive ballots. Once voters receive their ballots, they must include the same numbers used on their applications for the ballots to be counted.

Longoria said many voters either missed the new ID portion on their mail-in ballot applications or did not provide matching ID numbers when returning their ballots. Additionally, Longoria said a privacy flap aimed at protecting voters’ ID numbers has likewise caused issues.

In May, Texas Secretary of State officials unveiled new mail-in ballot envelopes that highlight the ID portion on the ballot with a large box, but Longoria said she believes its placement beneath the privacy flap could still lead to rejections.

According to Taylor, the privacy flap is required by law to protect voters’ ID numbers.

While Harris County’s mail-in ballot rejection rate dropped from 19.2% in the March primaries to 9.9% during the May 7 local elections, Longoria said she does not expect the decline to continue in the midterm elections.

“[Local elections usually have] a much smaller electorate, and they tend to have the most focused, highly educated, informed voters, so [those voters] are probably more aware of the provisions,” Longoria said.

In Montgomery County, roughly 6.2% of the 5,142 mail-in ballots sent in during the March primaries were rejected, up from 0.23% in the 2020 presidential election. By the May 7 election, the county’s mail-in ballot rejection rate dropped to 0.67%.

According to Montgomery County Elections Manager Estela Sánchez, the county’s declining rate of rejections can be attributed to an insert officials included with every ballot-by-mail kit providing step-by-step instructions.

During a May 7 local election determining two commissioner positions for Harris County Emergency Services District No. 11—which provides services in portions of Humble—the winner of the last at-large position won by 84 votes. Of the 2,784 mail-in ballots sent in the contest, 484 were rejected.

Additional barriers

Montgomery County Elections Administrator Suzie Harvey said the introduction of the new mail-in voting requirements has created challenges for older and disabled voters. Under SB 1, mail-in ballot corrections must be made in person or through the state’s online mail-in ballot tracker.

“Some of [those voters] can’t do either of those, whether it’s because they’re confined to some type of medical facility or housebound, or are technologically challenged,” Harvey said. “Sometimes, when our staff interacts with them, they are so frustrated that they just say they’re not going to vote anymore.”

Longoria cited similar concerns with Harris County residents using the state’s website.

“If the state doesn’t have your correct driver’s license or Social Security number on record—which is what they want you to correct—you cannot access the state’s website,” Longoria said.

Additionally, Longoria said individuals in the military or residents living overseas can be cut off from making corrections to mail-in ballots if they cannot correct them on the state’s website.

“You can’t come in and cure your ballot,” she said. “The only way you have to engage in voting is gone.”

Taylor said state officials have worked to address those concerns and many issues encountered during the March primaries have since improved.

Searching for solutions

Going into the Nov. 8 midterm elections, Longoria said officials are creating new protocols to keep the county’s mail-in ballot rejection rate from rising.

“We’re getting better at calling folks and instructing them on how to come in and correct their mail ballots,” Longoria said, noting her team is implementing improvements to help election officials track forms internally.

In April, Longoria announced she was resigning from her position after officials revealed 10,000 mail-in ballots were not entered on the March 3 primary election night. County officials had not named Longoria’s replacement as of press time June 21.

In Montgomery County, Harvey said the county will continue to include the informational inserts in mail-in ballot kits and train staff members to process ballots and assist voters more efficiently.

Heading into November, Taylor said the state is preparing a two-month campaign that will reach out to senior centers and senior living facilities to provide guidance to those who may be affected by the new mail-in ballot requirements.

Renee Cross, senior director of the Hobby School of Public Affairs at The University of Houston, said while it is hard to determine whether mail-in ballots issues will persist, voter turnout during the March primaries suggest SB 1 may not lead to the voter suppression its opponents have feared.

“I think in some ways, just the added attention of new laws [in the media] and the threat that it could suppress voting ... actually had the opposite effect and made people turn out,” Cross said.