More than 32,000 acres of land in the Katy area were flooded during Harvey, leading to more than 13,000 Federal Emergency Management Agency claims, according to previous Community Impact Newspaper reporting.

Katy-area neighborhoods affected by Harvey in August 2017 included Bear Creek Village, Barkers Crossing, Mayde Creek Farms, Winsor Park Lakes and Canyon Gate, which flooded when the Army Corps closed the Addicks and Barker reservoirs’ gates to hold water in the dam, as instructed by their operational guidelines, Community Impact Newspaper reported in February 2020.

“That’s the big challenge we have here,” said David Mackintosh, the Army Corps’ Houston project office chief. “People didn’t know what Addicks and Barker [dams] were. ... And they definitely didn’t know which side of the embankment they lived on.”

In December 2019, the Army Corps settled a lawsuit alleging it unlawfully flooded 10,000 properties upstream of the reservoirs in the days after Harvey. Another lawsuit on downstream damages was dismissed, and the upstream lawsuit is still determining damages. Mackintosh said the dams functioned as intended during Harvey.

“Our mission is to reduce the risk of flooding in downtown Houston,” Mackintosh said. “That’s our mission as congressionally authorized by law.”

Meanwhile, Harris and Fort Bend counties have struggled to gain external funding to match their respective 2019 flood bonds. So far, three of four Katy-area projects in Fort Bend County’s $83 million bond are complete, and the fourth is progressing—but 10 other bond projects remain unfunded.

Mark Vogler, the Fort Bend County Drainage District general manager and chief engineer, described his county’s bids for external grants as “wishful thinking.”

“These projects were just so, so massive in cost that the county was saying, ‘We don’t have the funds right now to do this bigger project—but let’s see if we can get a grant, and if we [can], maybe we can move the project forward by percentage,’” he said.

Funding limbo

According to previous Community Impact Newspaper reporting in October 2019, the bond aimed to help the county leverage $186 million in federal funding for $268.9 million in projects, County Auditor Ed Sturdivant said. At this point, less than half of the funds are being used, Vogler said.

However, most bond projects, such as erosion repair and desilting, were meant to restore the areas to pre-Harvey conditions—not mitigate future flooding, Vogler said.

“It’s not going to be any better, and it’s not going to be any worse,” he said. “It’s going to be the same. The bond money was to put things ... back like they were [before Harvey].”

He said the county applied for $96 million from the Texas General Land Office in 2020 but learned in May it did not receive any grants. Harris County has faced similar hurdles.

After the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development denied GLO Commissioner George P. Bush’s request to allocate $750 million to Harris County in May, the county created the Flood Resilience Trust to collect $833 million to support mitigation projects. In early August, FEMA awarded the Harris County Flood Control District nearly $250 million to remove sediment in eight watersheds, including Addicks and Barker.

While FEMA funding was granted in August, the HCFCD has worked to remove sediment from both reservoirs since 2016 to rehabilitate channels upstream, HCFCD officials said.

“In the years to come, we anticipate additional desilt efforts within Addicks, Barker and six other watersheds thanks to the recent award of nearly $250 million in FEMA funds,” HCFCD spokesperson Sheldra Brigham said.

She also noted two upcoming community engagement meetings addressing the projects: a Sept. 23 meeting on Addicks and a similar Sept. 30 meeting on Barker.

While many Fort Bend County bond projects did not secure outside funding, others were fully funded by the bond or gained funding from FEMA or the Natural Resources Conservation Service. The Willow Fork and Cane Island erosion repair and desilting projects were completed in May 2021 and June 2020, respectively. The Peek Road bridge project, which is set to go to bid on Sept. 21, after press time, will repair Harvey damage.

“We’re always going to continue to monitor [for grants],” Vogler said. “Any time there’s grant money [available], we’d be interested in it.”

Dam replacements

Vogler said the future of Katy-area flooding depends on the Army Corps.

“If we have another Harvey today, the [Army Corps] hasn’t changed their mode of operation—to my knowledge—on Barker reservoir, so you’d have the exact same situation,” Vogler said.

Corps officials said the reservoir gates close when there are more than 2 inches of rain upstream of the dam or 1 inch downstream. Moreover, there has not been any new flood mitigation construction since 2017 that would change a major flooding event’s outcome, Mackintosh said.

The Water Control Manual—the code dictating the Army Corps’ processes in a flooding event—has not been altered since Harvey except to update verbiage reflecting the Army Corps’ new dam outlet structures. New replacement dam outlets at Addicks and Barker reservoirs were built after studies revealed damage had occurred to the dam outlets over time.

“[The manual] is something we do review, but currently the only updates to the Water Control Manual are reflecting the new structure as opposed to the old structure,” Mackintosh said.

The new structures came after the dams received a “very high” Dam Safety Action Classification rating in 2009, which recommended “immediate action” before a failure occurred. The rating indicated the potential loss of life or economic consequences, combined with the likelihood of the dams’ failure, was at a rate unacceptable to the Army Corps, Mackintosh said.

Receiving the classification helped secure $84 million in federal funds to replace both structures at the reservoirs. Mackintosh said construction began in 2015 and was mostly complete in 2020; Barker’s structure became operational in February 2020 with Addicks’ up in March 2020.

“We needed to replace the structures and build them to do what they’re actually being called on to do, which isn’t what they were originally designed to do,” Mackintosh said. “The original structures were ungated and were designed to serve as flow restrictors during heavy rain events."

Gates were added to the structures to allow them to hold more water and regulate flows downstream. This resulted in more frequent, longer-lasting and larger pools—placing stress on the original structures’ foundations and increasing the potential seepage around them, he said.

Although the new dam outlets are built, Mackintosh said the Army Corps is always reviewing its processes—especially with Katy’s changing landscape.

“With all of this development that has happened, what does [flooding] really look like?” Vogler said. “When this was all pasture and rice fields, the water moved a certain way across here. It is not going to move that same way now.”

Risk Rating 2.0

While officials are working to mitigate flooding, Texas residents who insure their properties through the National Flood Insurance Program could soon see a cost increase.

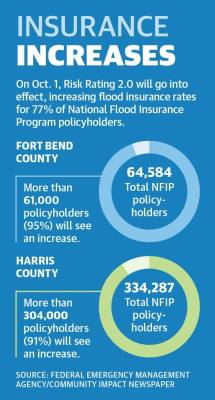

In April, FEMA announced a new methodology to determine a property’s flood risk. Dubbed Risk Rating 2.0, the change will take effect Oct. 1, increasing rates for 77% of policyholders, FEMA estimated.

More than 95% of Fort Bend County’s 64,584 NFIP policyholders will see an increase as well as 91% of Harris County’s 334,287 policyholders, FEMA officials said.

For renewed policies, the change will go into effect on April 1, 2022; but it is federally mandated that a flood insurance premium cannot go up more than 18% per year, FEMA said.

In the first year of the new method, 95% of NFIP policyholders in Fort Bend County will see a $10 to $20 increase, whereas 87% of Harris County policyholders will see a $0 to $10 increase. Sugar Land and Missouri City have publicly opposed the change, but Katy officials said they did not have a stance.

“The new rating method will provide more equitable insurance rates to better reflect a property’s flood risk by considering new flood risk factors,” Katy Project Engineer Ramiro Martinez said. “The new methodology may have an impact [on premiums.]”

The Fort Bend Economic Development Council, however, spoke against the change at its Aug. 19 meeting. FBEDC President Jeff Wiley said it was a risk for residents in flood-prone areas who will have to potentially pay more for flood insurance, which can be required to secure a mortgage.

“[The change] obviously impact a lot of property value and the marketability of those homes,” Wiley said.