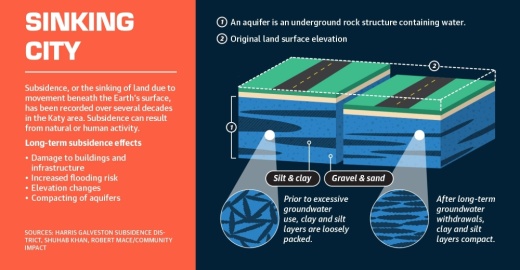

This gradual, vertical decline of Katy’s surface is known as subsidence, or the sinking of the land due to movement beneath the earth’s surface. Katy’s sinking is chiefly caused by pumping water from underground reserves, which compacts sublayers of clay and silt in aquifers beneath the Earth’s surface, according to the UH study.

Shuhab Khan, a geology professor at the University of Houston and one of the report’s authors, explained there is a balance to using groundwater sustainably.

“Groundwater is the cleanest water all over the world,” Khan said. “It is a means for drinking, for agriculture, for industry, and when we start pumping more water than the amount of water that is replenishing [aquifers], that balance is gone.”

Over time, subsidence can cause damage to property, pipes and roads, Khan said. It also makes an area more susceptible to flooding. Katy City Engineer David Kasper said the city is looking for ways to reduce the area’s reliance on groundwater, and while the city plans to take advantage of alternative sources, these options will not become available until 2026 at the earliest.

“We expect to receive surface water sometime between 2026 and 2028, thus reducing our use of groundwater supplies,” he said.

Though the conditions that cause subsidence can be lessened by cities using alternative sources, such as surface and potable water, the effects of subsidence are permanent, said Robert Mace, water policy director at Texas State University.

“If you reduce your pumping, you can then decrease the maximum subsidence that would have occurred,” he said. “But for the most part, land subsidence is a one-way trip. Once it’s compressed, it’s not coming back up.”

Study findings

The UH report found the Katy area’s population growth, development and geological characteristics affect subsidence, but the biggest contributor was the use of groundwater from aquifers.

Wells can be drilled into an aquifer, a large, underground water-bearing rock, and water can be pumped out for use by residents of a city.

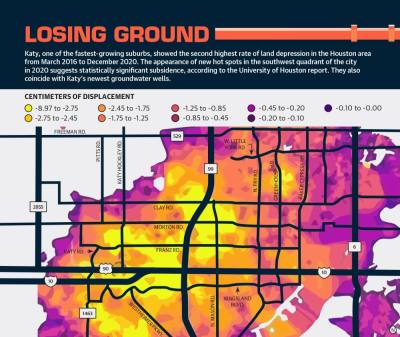

Khan’s report analyzed subsidence data in the Houston region from 2016-21.

“This [is happening] all over Katy,” Khan said.

Data from the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District, which regulates groundwater and monitors subsidence in Harris and Galveston counties, supports the study’s findings.

The UH report also measured groundwater levels below the surface of Katy and other Houston suburbs from 1990-2021. The aquifer water level was around 65 meters below the surface in 1990, compared to 110 meters below ground in 2021.

Even further, the report pinpointed new hot spots of subsidence in the southwest quadrant of the Katy area, coinciding with one of the city’s seven water wells in Waller County. The city’s 2021 drinking water report states the water wells have a combined storage capacity of 7.25 million gallons.

Ashley Greuter, director of research and water conservation for the HGSD, confirmed GPS data indicates the impacts of compaction in the aquifer associated with groundwater development.

In the past four years, mapping data from the HGSD found a 6.8-centimeter depression in the same location as the Waller County water well.

HGSD General Manager Mike Turco said the Katy area is experiencing subsidence because it has seen population increases and continued development, which leads to more groundwater pumping to meet water needs in the area. Between 2011-20, the six ZIP codes that make up Community Impact’s coverage area—77449, 77493, 77494, 77441, 77450 and 77094—saw a 57.31% population increase from 246,673 to 388,036, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

The Katy Area Economic Development Council expects 41,466 more residents to join Katy and the surrounding region by 2027, per Esri geographic data.“Subsidence that we see at the land surface is pretty consistent [across the area],” Turco said.

Potential effects

Turco said subsidence has contributed to flooding across the Houston area.

“These [flooding events] are in the same areas where we are seeing subsidence rates at 1 1/2 to 3 centimeters per year,” he said.

Mace, with more than 30 years of water policy experience in Texas, said the doughy geological sublayers of the Houston region and its flat landscape contribute to subsidence.

Damage to homes and buildings may occur along active faults—a fracture or zone of fractures between two blocks of rock—where differential subsidence can occur, Mace said.

“We have geologic variations, and we have these faults, where [land will] subside more on one side than the other,” he said.

If ground pumping trends continue, faults near the Katy area, such as the Addicks fault line near the Barker reservoir in southeastern Katy, will likely become reactivated or increase in activity over time, Khan’s report concluded.

Experts also warned excessive groundwater pumping will make flood mitigation more difficult in an area where it is already challenging.

Excessively extracting water from beneath the earth causes the land’s surface to sink. Even inland cities are impacted by subsidence, which contributes to changes in drainage patterns, flooding, fault movement, and damages to wells and pipelines, according to the HGSD.

Alternative sources

Katy’s land sunk a total of 7.2 inches from 2008-16 and another 4 inches from 2016-21, Khan’s report and HGSD data shows.

However, local water authorities, such as the West Harris County Regional Water Authority and the North Fort Bend Water Authority, are monitoring groundwater usage and working to wean cities off it as the primary source for drinking water and utilities.

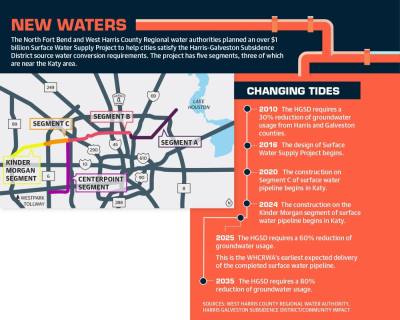

To address subsidence, they are collaborating on a $1 billion surface water pipeline that will run from Lake Houston to North Fry Road near Grand Parkway, under construction since 2020.

At a July 28 special meeting, Katy City Council approved a resolution with the WHCRWA to receive 3.6 million gallons of potable water to three of the city’s water production facilities as soon as the surface water supply pipeline is completed—in late 2025 by the WHCRWA’s earliest estimate.

The Surface Water Supply Project, jointly funded by the NFBWA and the WHCRWA, consists of large water transmission lines and two pump stations designed to convey surface water from the treatment plant at Lake Houston to entities and cities within their respective jurisdictions.

The project’s purpose is to meet the HGSD’s groundwater reduction requirements for 2025 and beyond—to eventually only use groundwater for 20% of a city’s operations, according to the SWSP team.

In 2013, the HGSD set requirements for all water suppliers in Harris and Galveston counties to reduce groundwater pumping based on the rate of subsidence in their area. The city of Katy must cut its groundwater usage 60% by 2025 and 80% by 2035, according to the HGSD’s regulatory plan.

Construction on the Katy portion of the pipeline—west of Beltway 8 to north Fry Road—began in 2020 and will be completed in late 2023, the SWSP team said. Kasper wrote in a July 28 memo the benefit of early conversion to surface water would be slowing land subsidence in the areas near the city of Katy’s water wells, but the four wells in Waller County will need to remain operational at their full capacity.

“Depending on the location of the development activity, it is possible that the city would need to construct a new water well in Waller County even if surface water supplies are available at the city’s facilities in Harris and Fort Bend counties,” Kasper said in the memo.

Khan sent his report to Katy officials to encourage an open dialogue about his research.

“Finding out about subsidence now is good,” Khan said. “Once you know a problem, you take steps to cure the problem before it gets too late.”