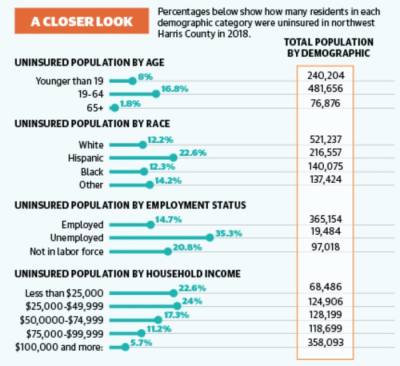

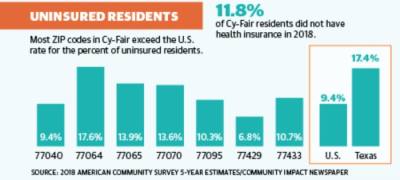

Texas has the highest percentage of residents without health insurance in the nation at 17.4%, compared to the U.S. average of 9.4%, according to 2018 census estimates. This amounts to 4.76 million uninsured Texans.

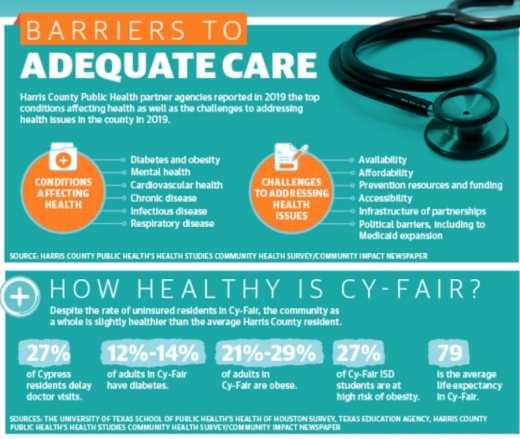

Arts and entertainment, food services, construction and retail are northwest Harris County’s employment sectors with the highest rate of uninsured workers, according to the census. Such industries were also hit hardest at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and continue to face layoffs, according to Texas Workforce Commission data.

Economy experts and local community leaders said they anticipate higher uninsured rates to follow the region’s spike in unemployment.

“Of the people that are coming for help right now, whatever their situation, there are so many people right now who have never needed assistance before,” said Janet Ryan, the director of development for Cypress Assistance Ministries, which supports Cy-Fair’s unemployed population, families in financial crisis and other individuals in need.

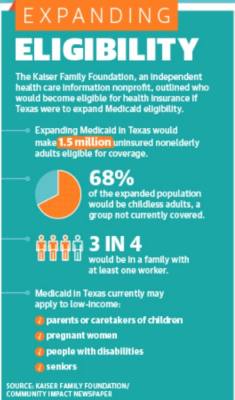

Health care and policy experts also point to Texas’ hesitancy to expand Medicaid eligibility—as outlined by the Affordable Care Act—as a contributor to the state’s large uninsured population. According to a report from the independent health care information nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation, 1.5 million currently uninsured nonelderly adults would be covered if the state expanded eligibility.

“If we were to do Medicaid expansion right now, we would not only pick up a million and half of those adults who are already uninsured, but potentially the million or more who may have found themselves on the uninsured rolls in the last month or so would have an option,” said Anne Dunkelberg, the associate director of the Austin-based Center for Public Policy Priorities.

COVID-19 complications

Residents without health insurance in Cy-Fair may be eligible for treatment at community-based clinics that charge uninsured individuals on a sliding scale based on their family size and income, such as the Spring Branch Community Health Center’s Cy-Fair location on Westgreen Boulevard.

SBCHC CEO Marlen Trujillo said most patients in the network of clinics qualify for federal assistance.

The clinics offer medical, dental and behavioral health services. Case managers also help patients determine if they are eligible for resources such as Medicaid or Medicare.

“A big part of it is not knowing how to navigate our health care system because our health care system is a bit complicated,” she said.

The process of walking patients through their options became even more complicated when the coronavirus pandemic hit.

Not only did virtual doctor visits become more prominent, but the assistance qualification work that would typically be done in person moved to phone calls and emails. Trujillo said it was a challenge to do so remotely.

SBCHC offers COVID-19 testing at its Spring Branch clinic, and Trujillo said she is working with city and county officials to expand testing. But even more than a lack of access to testing, a lack of understanding of the virus’s severity is hurting low-income families, she said.

“One family in particular that I know of went to the flea market over the weekend ... not wearing face coverings and surrounded by many people,” she said. “And then the other challenge that we’re seeing with our patients that are testing positive is that it’s really hard to isolate and self-distance when you have a family of six or eight living in a one-bedroom apartment."

Trujillo said SBCHC is preparing to add health care providers in the fall to accommodate the demand.

Long-term effects

CAM is able to support low-income individuals and families with essentials such as food, rent and utilities but cannot help with medical bills. Hospital systems, including Houston Methodist and Memorial Hermann, have set aside funds for uninsured individuals, but Ryan said sometimes these funds go unused simply because people are not aware of the assistance programs.

Because low-income families may struggle to purchase healthy groceries, a poor diet is one of the biggest contributors to poor health, Ryan said. According to county data, about 21%-29% of Cy-Fair residents are obese, and 12%-14% have diabetes.

“[Inexpensive groceries are] typically things like ramen and macaroni and cheese,” she said. “If you have $50 a week to feed your whole family, that really limits what you can buy. You buy what’s cheap, and what’s cheap is not good for your health.”

Additionally, with about 27% of Cypress residents delaying regular doctor visits, according to data from Harris County, uninsured patients especially may have underlying conditions that go undetected.

“When you’re sick, as your health is affected by that, you don’t have money to go to the doctor, so you procrastinate,” Ryan said. “You put it off until it’s not a concerning issue [but] a life-threatening situation.”

Potential policy changes

An April 27 report from the Kaiser Family Foundation shows 36 states have adopted Medicaid expansion, while the 14 other states including Texas have not opted into Medicaid expansion.

Trujillo said SBCHC would support the expansion of Medicaid to increase access to health care in the communities it serves.

“[Our patients are] a mixture of individuals who don’t qualify for Medicaid ... but they don’t have health insurance,” she said. “They can’t afford the employer coverage or their employer doesn’t offer insurance benefits, but they still make a little bit too much to qualify for Medicaid.”

In Texas, groups that may be covered under Medicaid include low-income individuals who are pregnant, who are a parent or relative caretaker of a child, who have a disability or a disabled family member in their household, or who are age 65 or older, according to Texas Health and Human Services.

“The idea under [the ACA] was you would subsidize coverage in the private market on a sliding scale for this really ‘working poor’ [group]. ... They’re just working folks, probably working two, maybe three jobs and just can’t afford health insurance,” said John Hawkins, senior vice president for advocacy and public policy with the Texas Hospital Association. “I do think the current situation really changes the playing field [for Medicaid expansion] for a variety of reasons.”

Rep. Tom Oliverson, R-Cypress, an anesthesiologist, said while he anticipates Medicaid expansion will be discussed in the upcoming legislative session—slated to resume Jan. 12—he also anticipates redistricting, unemployment and fiscal matters will get more of the focus.

“It’s a big-ticket item, and the question is, philosophically, whether or not it’s appropriate for the state government to be providing free- or reduced-cost health insurance for able-bodied adults who don’t currently have coverage through their employer,” he said.

Oliverson said his concerns with traditional Medicaid expansion include that few Texas physicians accept Medicaid and that expansion of Medicaid would be costly for the state.

However, Dunkelberg said she believes the ongoing pandemic changes the Medicaid discussion.

“The shape of this disaster may help ... because you have literally millions of Texans who maybe have never been jobless before suddenly overnight being thrown into that situation,” she said. “So when millions of Texans suddenly discover that because they have no income, they don’t qualify for anything, you may have a change in the political pressure.”

Adriana Rezal and Hannah Zedaker contributed to this report.