The Texas Wildlife Rehabilitation Coalition takes in about 4,500 animals annually from high-growth areas of the Greater Houston area, including Cy-Fair, Katy and Memorial. Executive Director Mary Warwick said many of these rescues are due to people invading animals’ territories—from birds who have their nests destroyed when trees are trimmed to baby opossums whose mothers are hit by vehicles, she said.

“Every year we get an increase [in animal rescues],” she said. “As the suburbs continue to grow, we’re using up more and more of their habitat, and so they don’t have anywhere to go.”

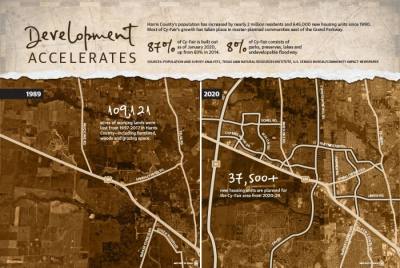

Fewer than 25 square miles of the Cy-Fair region are left undeveloped, and more than 37,500 new housing units are planned for the area from 2020-29, according to demographers at Population and Survey Analysts.

This includes nearly 18,500 single-family homes and 17,200 multifamily units mostly located within master-planned communities south of Hwy. 290 and east of the Grand Parkway, including Bridgeland, Dunham Pointe, Canyon Lakes West, Towne Lake and a future development owned by Landmark Industries.

Developers in these communities have incorporated natural elements residents and animals alike can enjoy. Heath Melton, the executive vice president for master-planned community residential development at the Howard Hughes Corp., said hiking and biking trails, parks and open space are among the top amenities homebuyers are seeking in Bridgeland.

“The dedication of open space ... is not a requirement. That’s something we elect to do so we can make sure that we provide areas where we’re either restoring nature or attracting nature and also giving our residents a place to really engage with nature as well as [for recreation],” Melton said.

State of local wildlife

Diana Foss, a Houston-based urban wildlife biologist with the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department, assists city and county agencies, developers and private landowners seeking to enhance their properties for wildlife.

Leading up to the construction of a major new project, a developer clears off the property to plot out where homes and other infrastructure might be placed on a clean slate. Foss said animals such as frogs, turtles and lizards might not survive this clearing of land, and animals that do make it out are tasked with finding a new home.

“The problem comes when they get to that new habitat because, most likely, there’s already animals using that spot, so there’s some competition going on. It’s survival of the fittest,” she said. “When they’re in their original habitat, they’re there for a reason—because they have plenty of food, water, shelter and space.”

Harris County has grown by nearly 2 million residents and 645,000 housing units since 1990, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Much of this growth has taken place in the northwest area, including Cy-Fair.

As new infrastructure is established in these growing areas, Warwick said native plants are critical for a healthy animal population. Squirrels and birds find secure homes in mature trees, and smaller creatures in the food chain have access to pollen from native plants, she said.

Harris County lost about 27% of its cropland, timber and grazing space from 1997-2017, according to a report from the Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute. But during the same time frame, the county saw an increase in space reserved for wildlife management.

Several programs highlight nature locally while incorporating multiple uses, including the Cypress Creek Greenway Project, which was designed to preserve existing natural habitats, provide opportunities for recreation and reduce flooding along the creek.

“If you look at your property and you block off those areas and say, ‘We’re not going to bulldoze that; we’re going to protect that and use that as part of a green space for the neighborhood,’ ... everybody’s going to be happy,” Foss said.

Developing responsibly

Foss said it is best to identify potential ways to develop around the existing habitats before clearing the space. If there is a pond on the property, for example, wildlife will benefit from maintaining a water source, and future residents of the neighborhood can access the pond for fishing.

Bridgeland has about 4,000 homes with another 3,669 housing units planned through 2029, according to PASA. Melton said 28% of the community’s 11,400 acres are dedicated to parks, lake trails and green space.

One example of responsibly developing with the natural environment in mind is turning required detention areas into amenity lakes residents can use for kayaking, canoeing and observing native wildlife, Melton said.

Additionally, Bridgeland developers have restored the former deforested farmland to the prairie-like environment it once was by bringing in native plants and reforesting to create additional habitats for squirrels, raccoons, deer and migratory birds such as pelicans.

“It was a very manicured landscaping 13 years ago when the community started, and we’ve transitioned to a much looser native landscaping,” Melton said. “We have areas that [are] all native plant materials and grasses that we let grow.”

When it comes to major transportation projects, officials with the Texas Department of Transportation said they take several environmental factors into account. Preemptive studies for the Hwy. 290 project included vulnerable species and wetlands in the pathway, said Deidrea George, a public information officer with TxDOT’s Houston District.

George said TxDOT works with the TPWD to develop best management practices during and after the construction process. For instance, the clearing of vegetation might be put on hold during nesting season, or officials will survey the area to ensure no active bird nests are disrupted.

“Where possible, the roadway is designed to avoid these resources,” she said. “Where impacts are unavoidable, the department works to minimize and/or mitigate the impacts.”

Discovering nature’s benefits

While living among nature is a necessity for animals, it is also a priority for many people, Foss said, and home values are typically higher in neighborhoods located near natural parks and open spaces.

“People need green space, too. We need to look out on something pleasing,” she said. “It’s beneficial to our health in many ways—it lowers our blood pressure and our stress hormones ... when you look at something green, something natural.”

According to data from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 41% of Americans spent a total of $157 billion on hunting, fishing and wildlife watching in 2016.

Some Cy-Fair residents, including Frankie Schwarzburg, make the most of animal visits by creating an educational opportunity for their children.

“We didn’t know anything about [opossums] at first,” Schwarzburg said. “My daughter has fell in love with them. She has learned how their hands work, how they use their tail.”

Animals can thrive better in their natural environment than in the care of humans, Warwick said, and residents should consider the benefits wildlife can bring—such as opossums getting rid of ticks.

“Don’t invite nature in, and don’t feed them unnatural food in your yard. But also don’t kill them, and don’t get rid of them,” she said. “They’re there for a reason; they’re there for a benefit for everybody.”