The amount of cats and dogs that become lost, surrendered or abandoned in the community goes up along with that human population growth, creating a strain on its ability to house those animals, according to City of San Marcos Animal Services.

Animal Services defines the live outcome rate for cats and dogs as those that were successfully adopted, transferred to another rescue shelter, returned to their owner or otherwise serviced out of the shelter.

According to SMRAS statistics, cat and dog live intakes clocked in at 4,059 for fiscal year 2020-21 and yielded a 92% live outcome rate. Compared to FY 2018-19, where both the live intake rate was lower, 3,840, along with the live outcome rate, 85%, the shelter would seem on track to maintain its stated goals. The live outcome rate for FY 2017-18 was 78%.

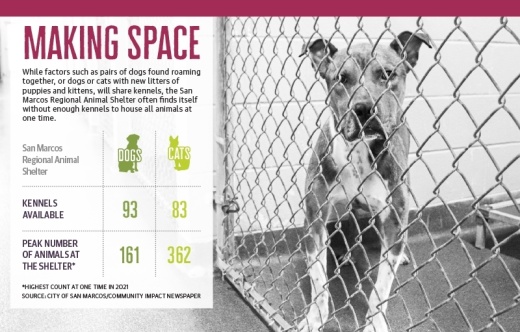

However, the number of available kennels and space in the facility puts a strain on the system.

The average length of stay from Feb. 1, 2021-Feb. 1, 2022 was 32 days for cats and 18 days for dogs, Assistant Director of Neighborhood Enhancement DerryAnn Krupinsky said.

“We use that data more internally as well as intake data to get a more accurate picture since length of stay can easily be skewed by the number of litters that are too young for surgery [and therefore adoption] or animals undergoing lengthy medical treatment [such as dogs with heartworms],”she said.

The SMRAS has 83 cat kennels and 93 dog kennels, Krupinsky said. From January 2021 to January 2022, the average number of animals in the shelter system was 192 cats and 115 dogs. The highest point-in-time count within that period was 362 cats and 161 dogs, according to an annual report from Animal Services.

“We can expand that for temporary holding using smaller pop-up cages, and of course, foster homes,” Krupinsky said.

The kennel-to-animal ratio is not always one to one, as some situations where the animals are familiar or get along might mean they can be paired, said Christie Banduch, interim animal services manager for the SMRAS. Banduch was recently named animal services manager and officially begins that role later in March. The shelter does not house unrelated animals together and does not house opposite sex animals that are not altered already together, Banduch said.

Banduch said that if for instance two male dogs that were found running together, they would go in the same kennel together, as they would not breed and are familiar with each other.

“It’s kind of like the buddy system for those guys where you’re not all alone in the shelter. If we have a mother with puppies or kittens, they’re obviously going to be housed together,” Banduch said. “We just have to kind of make those decisions based on each individual animal or group of animals that comes in, who should stay together in a kennel and who maybe needs to be separated for their time here. So there’s a lot of variables there.”

A 92% live outcome rate still means 8% of cats and dogs do not leave the shelter alive. In 2021, 10 cats and dogs went missing or lost, 100 died in care and 206 were euthanized.

But euthanasia is not warranted by length of stay alone, Krupinsky said.

“Every pet is unique. There are some that are comfortable in the shelter environment for any length of time. We watch for changes in behavior, appetite, weight loss and medical issues. At that point we would try medical intervention, rescue plea, and/or assess for foster placement,” she said. “Humane euthanasia is used to end medical suffering or when the animal is a danger to itself or people.”

Funding the shelter

While the SMRAS is in San Marcos, managed and staffed by the city, its funding is allocated through not only general fund coffers of the city of San Marcos but also Hays County, Buda and Kyle, as they transport animals collected in their jurisdictions to the SMRAS. That funding is allocated annually based on the percentage of use—or intake of animals from each area—in each municipality, with San Marcos usually being close to half of the source of all new intake animals. The total funding for the shelter for FY 2020-21 was almost $1.5 million, according to city documents.

The Hays County Commissioners Court awarded a contract Feb. 15 to Team Shelter USA, a national animal welfare consulting firm, to study what needs exist in Hays County for animal services, including whether another shelter might be warranted.

“The regional shelter has continued to get overcrowded, especially with all the changes that have been made to try to get a greater percentage of no kill. And that has put a lot of stress on our shelter, and all the partners understand that,” Hays County Commissioner Lon Shell said.

Shell said that the county recognizes additional sheltering services or additions to the existing shelter or modifications will be needed in the near future in order to accommodate growth in the county, as well as to achieve higher “no-kill” percentages.

Shell said the idea of hiring a consultant arose from wanting outside experts to look at the unique circumstances that exist locally and determine the best course forward, be that a new facility or multiple facilities to aide in alleviating current and future constraints on animal services.

“They’ll get going and start meeting with folks, doing their due diligence and research. And then I’m hoping that by the end of the summer we could have [something] deliverable,” Shell said.

Other resources for animals

While the SMRAS is the only public intake shelter in Hays County, there are other shelters and organizations that help alleviate overcrowding and fostering of animals that end up in the system.

PAWS Shelter of Central Texas was founded in Kyle in 1986 and opened a second shelter in Dripping Springs in 2019. The nonprofit shelter predates the SMRAS, and while not an intake shelter, it does help adopt out cats and dogs that begin in the SMRAS system as well as those that come from elsewhere.

With the new shelter in Dripping Springs, however, PAWS has done some open intake that it felt was necessary, Executive Director Melody Hilburn said. “We would not normally open intake; we’re just trying to support the community over there, because they really don’t have anything other than a 50-mile drive [to SMRAS]. So, when a stray comes in, then we go through the regular process of checking them out physically, posting them on all of the numerous lost and found boards out in Hays County and Blanco [County],” Hilburn said.

The Kyle facility still refers people who bring in animals they found or want to surrender to the SMRAS, Hilburn said. As a no-kill shelter, PAWS [and Austin Pets Alive] keeps animals for as long as it needs to but does not take in any more than it can handle at one time. When it does have room, it will take animals from the SMRAS to help alleviate the burden.

PAWS was also part of a cohort of organizations that helped guide the SMRAS—as part of a 2018 initiative by San Marcos City Council and other entities—to implement volunteer and foster programs to help alleviate overcrowding.

“PAWS, [Austin Pets Alive] put together a task force that went into the San Marcos shelter because they had no foster programs, no volunteer programs, and we really shared all of our tools, to help them get closer to a no-kill initiative. Because you can’t do no-kill without fosters and volunteers, and it takes a village kind of thing, you know?” Hilburn said. Sharri Boyett, Hays County animal advocate and community liaison, said putting all these pieces together will help achieve the goal of getting the SMRAS to no-kill status.

“The good news is the live outcome rate, which is the goal for 90% or more. That’s the typically accepted definition of what a no-kill is. But to do that, you have to have a long, sustained commitment to not euthanize for space, and to implement programs for community cats and compassionate leadership and volunteer participation. Those things are not necessarily happening the way they are. It’s a component to the no-kill equation,” Boyett said.

Other efforts by cities and advocacy groups could lead to fewer animals in the system, such as regulations on commercial pet sales, as was considered recently by San Marcos City Council but ultimately tabled, said Stacy Sutton Kerby, director of government relations with the Texas Humane Legislation Network. City Council is expected to revisit the issue. It was modeled on a bill in the 87th Texas Legislature—House Bill 1818— that did not make it through the 2021 session. The regulation would require publicly visible documentation of where every animal is sourced from and maintain that record for one year following the date the pet store takes possession of the dog or cat, be it an animal shelter, private breeding facility or other source.

A record would have to be displayed next to the cage or enclosure each dog or cat is kept in detailing the name and contact information of its origin.

The new rule would have only applied to commercial pet stores, not individual breeders that raise dogs or cats in their home, according to the documents.

Kerby said restrictions on the sale of pets at pet stores that limit where the animals originate from, such as prohibiting pets from large out-of-state breeders, can help dampen the total number of animals that end up in the system.

“When you have a humane sourcing requirement in your local retail pet sales ordinance—that is if the pets have to come from animal services or shelter or a rescue group—that helps to alleviate pressure on the shelter,” Kerby said.