Groundwater districts conserve, manage and protect groundwater resources within the boundaries of the district, according to the SWTCGCD’s website. The SWTCGCD extends west from Austin and south of Lake Travis. It is the only entity in Texas with some degree of control over groundwater usage, Hunt said.

“Surface water is treated as a state resource. Groundwater, water beneath your property, is a private property right,” Hunt said. “How do you manage a private resource that really is a common pool resource? That’s the challenge for any groundwater district in Texas.”

Groundwater in the area is provided by the Trinity Aquifer, a limestone water-transmitting and -storing formation extending narrowly through Central and North Texas. Rain, bodies of water and other factors contribute to the level of water in an aquifer, depending on its location. Aquifers take a certain amount of time to replenish their supply of water following use.

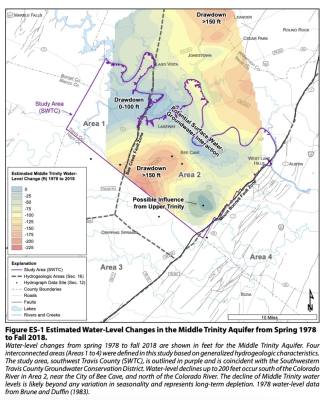

The Trinity aquifer is a complex series of geologic deposits, but the presentation focused on splitting the aquifer into three parts: the upper, middle and lower Trinity aquifers. The upper Trinity is shallow and at surface level, followed by the subsurface middle Trinity and underlying lower Trinity.

Wells in the upper Trinity rely heavily on surface water supplies such as rain and may go dry during a drought, but due to their ability to refill quickly, they are considered “renewable” water supplies. The middle and lower levels of the Trinity aquifer are slower to replenish, Hunt said. This has led to consistent depletion of groundwater resources of “nonrenewable” water resources.

From 1978 to 2018, the water level in the middle Trinity dropped from 150-200 feet in the area southwest of Bee Cave, according to the data. As water levels in the middle Trinity decline, wells must be dug increasingly deeper to reach groundwater.

“At some point, you can't lower your pump anymore, and you have to get a drill deeper,” Hunt said. “At some point, you're gonna run out of aquifer.”

The reason for such slow recharge is not entirely clear; however, recent research pinpoints two fault lines on either side as potential culprits, Hunt said. The Bee Creek Fault Zone and Mount Bonnell Fault sandwich the area southwest of Bee Cave, effectively isolating the aquifer. The area between the two faults has seen the most significant decrease in groundwater levels over time, according to the data.

“We’re drawing water out of rocks that are bound by faults; they’re constrained,” Hunt said. “Nothing is sure in science, but we think that these two features are part of the inherent reason why these rocks are not all that productive. They’re not going to rebound with the next 10-inch rain.”

After its creation by the Texas Legislature in 2017 and approval from voters in 2019, the district now receives funds for research to find out more about groundwater in the region.

Hunt and others are now working with The University of Texas to conduct studies on the area to determine more information about groundwater supplies.

“Surface water and groundwater are interconnected,” SWTCGCD President Richard Scadden said. “You can’t talk about one in isolation to the other. The general supply of water in our area is stressed, and this summer, it’s going to be really stressed if all the predictions are true, and we’re all going to need to conserve.”

Prior to the establishment of the groundwater conservation district, little to no data was available on groundwater in the area, Hunt said. Though data shows around 2,500 wells in the area, there is no solid number on how many wells exist in the district as registration was not required until recently.

Being a fledgling district, the SWTCGCD has enough struggles in getting wells registered, let alone monitoring their water levels, Scadden said. To get a better grip on where and how water is going, the conservation district is urging residents with wells to register them with the district.

“We certainly don’t have all the answers, and that’s part of why we’re doing all this,” Hunt said. “There is a lot of good information out there that you all contain, whether it’s observational, anecdotal or even just access to wells for points to monitor; I think we can increase our knowledge and hopefully help preserve the groundwater resources around here."

More information about the state of groundwater in southwestern Travis County is available in a report by Hunt and others here.