While these conditions are cause for concern, state of Texas Climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon predicts long-term drought, known as megadrought, could be in Texas’ future. This type of drought is different from the drought occurring in Travis County as well as the drought of 2008-15.

By the latter half of the 21st century, worsening long-term drought conditions in Texas could put strain on Lake Travis as a natural, recreational and financial resource for the Lake Travis-Westlake area and beyond, said Nielsen-Gammon and Jo Karr Tedder, president of the Central Texas Water Coalition.

Under these conditions, drought is the new normal, Nielsen-Gammon said. Restricted water use and lower lake levels become permanent fixtures in the life of Central Texans, and everyday activities such as lawn watering become a privilege.

To mitigate effects of long-term drought on Central Texas, climatologists and activists are calling for Texans to be vigilant of water usage and plan ahead.

“Be conscious that water doesn’t just appear from the tap,” Nielsen-Gammon said. “It’s stored, extracted and treated. Sometimes there’s plenty of water, and sometimes there isn’t. Being able to reduce water use is an important capability to have.”

Drought in Central Texas

Due to regional population growth, climate predictions and rain variability, the future drought in Texas may actually be a megadrought, which lasts at least two decades, Nielsen-Gammon said.

Megadrought is caused by natural climate cycles and human-induced climate change, which climatologists such as Nielsen-Gammon said will cause higher average temperatures that increase evaporation rates and affect the intensity of rainfall.

“Texas isn’t in a megadrought right now, but one is always possible,” he said. “Low [lake] levels will probably happen again sometime, but it depends on both the weather and on water use. There’s no telling when it will happen again.”

Rainfall variability also plays a large role in determining the likelihood of megadrought. Texas has historically had unpredictable rainfall patterns, making it difficult to predict when drought may occur, Nielsen-Gammon said. All the pieces are there, but whether they fall into place is dependent upon natural variability in the climate cycle.

“Whether or not we have a drought in any given year depends upon the rainfall in Texas,” he said. “Texas is quite variable from season to season, and year to year. We’ve had some decades with 50% more rainfall than other decades, for example.”

The unpredictability of drought has prompted activists such as Jo Karr Tedder, the president of the Central Texas Water Coalition, to call for more conservation efforts from entities such as the Lower Colorado River Authority, which manages water in the Highland Lakes. Most of the water for Bee Cave, Lakeway, West Lake Hills and Rollingwood is provided through contracts with the LCRA.

The Greater Austin area population grew 33.7% between 2010-20, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The region is expected to grow from roughly 2.2 million residents in 2020 to 4.5 million in 2050. This massive increase will strain the Highland Lakes system that provides water to the area, including Lake Travis and Lake Buchanan, Tedder said.

“It seems to be all coming together at a time when our water demands for the region are going to significantly expand,” Tedder said.

One particular area of concern is the decline of water flowing into the Highland Lakes. These declining inflows are caused by a multitude of factors, including the unregulated sale and use of water upstream, she said.

Though the state water plan has been in place since the mid-1900s, 25 years ago it started using a system that splits Texas into 16 regions, each of which develops its own plan that is then compiled into the state water plan. The Highland Lakes system is part of Region K, which stretches from the top of the Highland Lakes to Matagorda Bay.

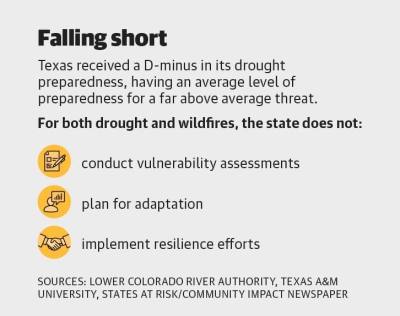

“The biggest flaw is that the [state water plan] doesn’t explicitly take into account climate change, at least not at the state level,” Nielsen-Gammon said. “But individual regional planning organizations are free to consider climate change.”

Impact on lake economy

When the drought of the early 2010s brought Lake Travis to historic lows, business owner Pete Clark said the hardest part was staying afloat.

“We’re talking about something I don’t think anybody saw coming,” Clark said. “And there’s nothing you can do about it except battle through it one day at a time.”

Clark said he lost five businesses as a result of the drought: Carlos n’ Charlies, Cafe Blue, Sandy Creek Marina, U Float Em and North Shore Marina. He laid off nearly 350 employees and lost roughly 70% in revenue.

Lake Travis is a significant economic engine, generating $207.2 million in revenue for state and local governments, $3.6 million in hotel and mixed beverage taxes and $45.2 million in sales tax from commercial businesses annually, according to the Lake Travis Coalition. When Lake Travis is low, people find other places to go, Clark said.

To protect his livelihood, Clark said he has in years since worked to diversify his revenue streams by opening businesses not reliant on water levels. In times of drought, the businesses operating at full capacity can offset those impacted by low lake levels, he said. He has also tried to make his businesses more resilient by growing his on-land customer base at his existing lakeside ventures.

“It’s going to hurt, and it’s going to leave a mark, but it’s not necessarily going to be devastating,” Clark said. “We just kind of go through life hoping to dodge bullets.”

Mitigating drought

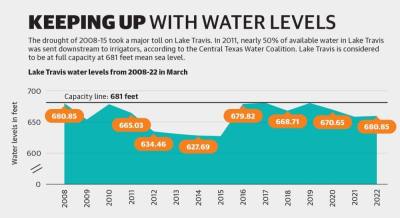

In 2011, nearly 50% of available water in Lake Travis was released downstream to irrigators for farming, according to the CTWC. After 2011, the LCRA put a system in place to prevent water being sent downstream to irrigators when needed for use by cities. The problem with this system is that Austin is good at conserving water, which makes it appear that there is more water available than there really is, Tedder said.

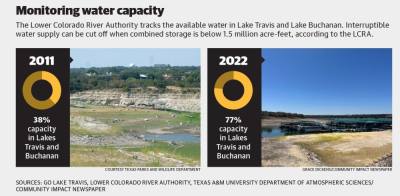

One acre-foot is equal to 325,851 gallons of water. •The combined storage of these two lakes is about 2 million• acre-feet when full. As of March, the combined storage of both reservoirs was at 77% capacity, according to the LCRA.

To prevent the overestimation of upstream water resources, the CTWC recommends the LCRA implement a “safe yield” system that would keep enough water needed to sustain cities in the upper basin for at least a year. The LCRA declined to comment for this story but released a statement that the plan in place is designed to maintain enough supplies for municipal water use even during the worst drought the region has seen.

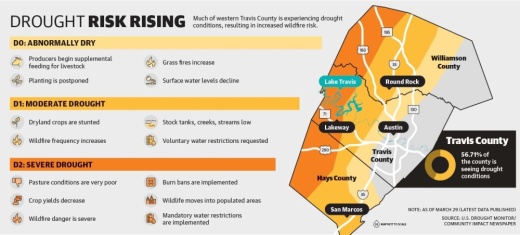

In addition to improved conservation efforts, it is also important to increase wildfire preparedness, said Will Boettner, Travis County wildfire mitigation officer. For western Travis County, the abundant greenery presents ample opportunity for a wildfire during a drought.

Western Travis County has few fire hydrants, so most fire trucks use water from attached tanks attached, Boettner said. During a drought when water levels in Lake Travis are lower, water pressures may be too low or water may become unavailable.

“That’s why we’ve become much more proactive with trying to prevent fires from ever getting started,” he said.

While the future of Lake Travis in the face of drought remains uncertain, it is key to keep looking ahead, Tedder said.

“It’s hard to get the word out and educate people about what’s really happening,” Tedder said. “You need to be doing your hard planning when there is plenty of water, because when you’re in a drought, it’s too late.”