Still, district officials and educators at Lake Travis and Eanes ISDs say the academic and emotional recovery from months of pandemic schooling will require multiple years of effort. As the upcoming school year quickly approaches, district administrators and teachers are working diligently to combat what the Texas Education Agency has deemed the “COVID[-19] slide,” or academic decline spurred by months of disrupted schooling.

One of those teachers is Kendall Sealy, who has taught seventh grade Texas history at LTISD’s Hudson Bend Middle School for roughly four years. Sealy—who was also LTISD’s 2020 teacher of the year at the secondary level—said she is looking forward to welcoming students back to the classroom, a portion of whom have never stepped foot on Hudson Bend’s campus.

While a majority of her classroom attended school in person, roughly 30% remained virtual last year, and Sealy said at times it was difficult to engage those students, some of which did not turn on their video cameras during class.

“Some of my most consistent struggles, from my perspective, are the difficulty of building relationships with kids that are virtual,” Sealy said.

Despite the challenges, Sealy and her colleagues worked diligently and creatively to conduct the most successful school year possible amid a global health crisis—still, the work is ongoing, Sealy said. Ahead of the upcoming school year, she said she and her colleagues are working together to predict any learning loss students might have.

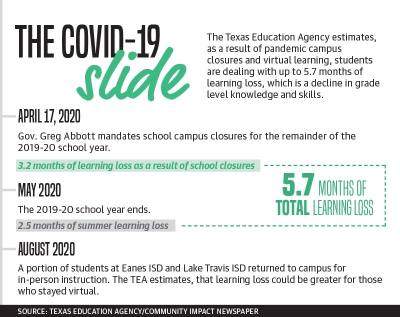

The COVID-19 slide

The term learning loss is nothing new for teachers. It typically occurs over summer break when Texas students lose on average 2.5 months of instruction, according to the TEA. However, coming off the heels of a pandemic, students could face a minimum of 5.7 months of learning loss based on an optional statewide assessment conducted at the beginning of the 2020-21 school year.

EISD Chief Learning Officer Susan Fambrough told Community Impact Newspaper she prefers to use the phrase “unfinished learning” when describing the academic impact of the pandemic. Heading into the upcoming school year, the districts will identify and rectify those gaps in instruction, she said.

“We really want to make sure that we’ve given all of our students the same opportunity to have that foundational learning,” she said.

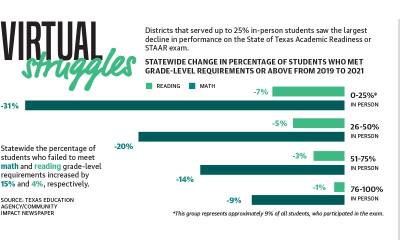

The State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness, or STAAR, exam can help educators pinpoint that “unfinished learning,” and according to Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath’s comments during a June 28 press conference, COVID-19’s impact caused record performance declines.

The most significant decline was demonstrated in statewide math scores—a trend reflected in results from both EISD and LTISD. Prior to the pandemic, Texas students had been steadily improving in the mathematics section; however, the number of students at or above grade level declined 15% from 2019.

That figure, while significant, is somewhat unsurprising when considering the subject material, Fambrough said. Mathematics is a sequentially taught subject, meaning that if a student does not understand or skips a certain skill, it can be hard to progress. Conversely, there was a 4% statewide decline in the number of students at or above grade level in reading, which Fambrough said is an everyday activity, so it contributes to the smaller decline.

At EISD and neighboring LTISD, a majority of students saw better STAAR outcomes on average than the state overall. For example, 10% of EISD seventh-grade students did not meet their grade-level goals in math compared to 46% of statewide seventh graders. According to the TEA, a student who receives a “did not meet” designation does not have enough understanding of the material.

“When we look at our kids, particularly in comparison to the overall score in the state of Texas, we’re doing OK,” EISD Superintendent Tom Leonard said.

Results from LTISD followed a similar pattern. Stefani Allen, LTISD assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction, attributed the better-than-average scores to several factors, including access to technology and a community of academically engaged parents.

“Overall, we wouldn’t experience the type of academic slide that maybe another school district would,” Allen said.

Higher-than-average scores do not suggest that students, particularly those who receive special education services, did not struggle with pandemic schooling, Leonard said. Still, EISD, a district with a comparatively low percentage of economically disadvantaged students, did not face the same hurdles as neighboring or more rural districts.

However, STAAR scores are just one of several metrics available to identify struggling students.

Fambrough said EISD will utilize quarterly benchmark assessments as well as the Measuring Academic Progress, or MAP, assessment, which tests kindergarten through 12th-grade students in core subjects and is administered multiple times per year.

“We really do believe that the STAAR assessment is just that—one assessment on one day,” she said. “We’re trying to take lots of pieces of data in order to help us figure out where our students are.”

Allen said LTISD will employ a similar approach. Students will take an assessment at the start of the 2021-22 school year to provide staff with an early look at potential gaps in instruction.

The most crucial tool in addressing learning loss, however, will be the teachers, and work is already underway at EISD and LTISD to create plans of action. Allen said all summer, staff have been working alongside teachers from every subject area to develop comprehensive plans for filling any academic gaps. Additionally, Allen said a large component of those plans is an effort to reintroduce instruction from the previous year.

“We’re looking at ways to spiral in previous years’ information, so our fifth-grade teachers will be spiraling in fourth-grade information as they’re teaching fifth grade,” Allen said.

At EISD, the main focus of summer staff development sessions was an effort to identify learning gaps, Fambrough said. Teachers were sectioned by grade level and asked to review data on their students’ academic progress. Once the gaps were identified, staff developed plans for intervention, which often include small group instruction. Additionally, those plans will encompass equally enriching activities for those students who do not lack in that skill set, Fambrough said.

Allen and Fambrough agreed that both districts unquestionably must focus on academic decline as a top priority. Yet, it is not the only challenge students are facing as a result of the pandemic—social-emotional learning, or SEL, is an equally important area of concern, they said.

Social-emotional loss

EISD describes SEL as the knowledge and skills necessary in managing emotions, achieving goals and showing empathy for others, among other attributes, and it, too, was altered as a result of the pandemic. EISD’s professional development encompassed a section devoted to re-engaging relationships with students in a trauma-informed classroom, meaning a teacher recognizes that a child may have gone through a difficult life event that could impact their academics.

Sealy, who is also working toward her graduate degree in school counseling, said students’ mental health is at the top of her mind. She said she is focused on conducting check-ins with students as well as providing them with social interactions and time to process their experiences from the previous year.

“Reminding them that school is a safe place and that they can be themselves,” Sealy said. “My classroom and our school campus is an accepting environment, and we want them to be honest about where their learning gaps might be or where they’re struggling socially [and] emotionally.”

Allen agreed and said the district as a whole has put an emphasis on the mental wellbeing of staff members, students and their families. LTISD will also fund additional positions to support this need, Allen said. These additional support positions will be made possible through incoming aid.

Funding an academic recovery

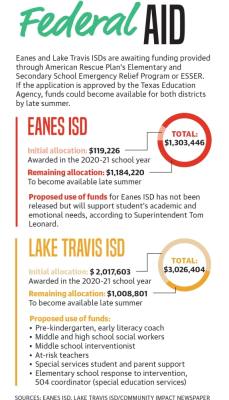

Addressing the emotional and academic needs of students will be no small feat, and both districts are leaning on federal funding provided through American Rescue Plan’s Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief program, or ESSER, which was passed in March.

The U.S. Department of Education released two-thirds of the federal aid to the TEA. LTISD Chief Financial Officer Pam Sanchez said districts received the initial round of funding the summer prior to the 2020-21 school year. The TEA used the second round to supplement the hold harmless provision, which ensured districts received state funding based on projected enrollment numbers despite any declines.

Both districts submitted applications to the TEA to obtain the third and presumed final round of ESSER aid called ESSER III. Once approved, they will receive roughly $1 million each, with funds available by late summer, Sanchez said. A minimum of 20% must go toward the academic impact of the pandemic. Districts can spend the remaining percentage for technology, facility updates or mental health support, among other resources.

ESSER funds can be used over a three-year period and officials at LTISD and EISD agree that a full COVID-19 recovery will require multiple years of effort on behalf of the district and its teachers.

Still, Fambrough said she is very proud of the work conducted so far, especially by the district’s educators.

“Our teachers, not only at Eanes but in the nation, are to be applauded for what they had to do this last year,” Fambrough said.