Early voting begins Feb. 14 the 2022 Democratic and Republican state primary elections to decide candidates in the Nov. 8 general election.

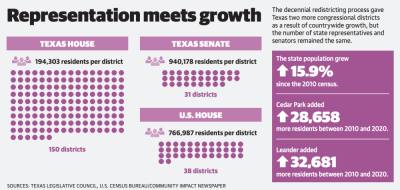

Representation changes in Cedar Park and Leander were a result of rapid regional growth in Central Texas and the partisan redistricting process in the Texas Legislature, said David Albert, a government professor at Austin Community College. Since the Republican party is in control of the legislature, maps were drawn in the party’s favor to increase its margins across the state, Albert said.

The Texas Legislature is required to create new district maps every 10 years to redraw state House, state Senate, U.S. congressional and State Board of Education districts. Gov. Greg Abbott approved the final maps in October and the new maps went into effect Jan. 18.

Political parties can use two techniques to create maps that benefit them: cracking and packing. Albert said cracking breaks up communities, for example, to weigh down liberal voter areas with more rural voters. Packing, which was done more in this redistricting process, maximizes the representation of a specific party in that district.

“The idea is to create safe districts for your party that will be won even in a relatively bad year for your party and then create safe districts for the other party that will have very high levels of their voters so that those voters are not the majority party’s district,” Albert said.

Primary elections will likely determine who wins the seat as districts are drawn to favor one party or the other, Albert said, though primaries historically have a lower voter turnout than the general election. Election races can become more competitive in the 10-year cycle as districts grow and change before the next redistricting process.

Divided districts

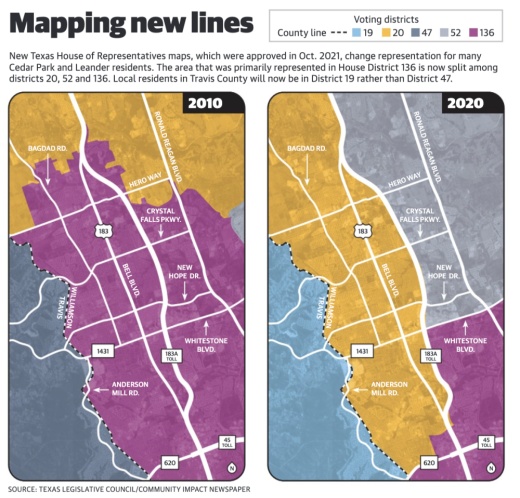

Large changes were made in the new Texas House maps in Cedar Park and Leander. Two districts represented a majority of Cedar Park-Leander residents: District 136 previously represented residents in Williamson County and District 47 represented residents in Travis County.

Now, four districts will divide the two-city area. District 19 replaces District 47’s coverage in Travis County, and districts 20, 52 and 136 will split Cedar Park and Leander in Williamson County.

These changes made District 136 a safer Democratic district and District 52 a Republican-leaning district, Albert said. As a result, District 52 Rep. James Talarico, D-Round Rock, chose to run in District 50 in North Austin instead.

District 136 represented most of Cedar Park, Leander and the Williamson County portion of Austin. New maps changed the district, which is represented by John Bucy III, D-Austin, to primarily include Round Rock, the Brushy Creek area and part of southeast Cedar Park.

Bucy, who is running for reelection to District 136, said several of his bills in the prior legislative session were for the city of Leander, which he will no longer represent. He said changes were coming as Williamson County saw significant growth in 10 years and the districts were overpopulated.

“It’s kind of a frustrating and fascinating experience to go through redistricting because you spend all your time really building up relationships in a community, and then overnight those lines are redrawn and things are shifted and you have new communities to work with immediately,” Bucy said.

The three house districts in Williamson County work closely together, Bucy said, and the offices will work together to help constituents find where they need to go as their districts change.

“It’s important that a regional delegation get along and work together,” Bucy said. “And that’s what we’ve done in Williamson County.”

A majority of Leander and Cedar Park will now reside within House District 20, which Rep. Terry Wilson is seeking reelection. District 20 will now cover a major portion of Cedar Park and Leander, Georgetown and northern Williamson County. The district previously represented Georgetown and areas of north and east Williamson County.

Wilson, R Marble Falls, said two similar issues between his old district, which included Milam, Burnet and part of Williamson counties, and new district are growth and rural water issues.

Cedar Park will be represented by four House districts, and Leander will lie within three House districts.

Wilson said Williamson County’s large population growth made it di fficult to keep communities of interest, such as cities and school districts, within the same district. He said having multiple representatives working on each city’s issues can be an advantage for each fast-growing city.

“At first we were like, ‘That’s tough because you don’t have that one representative that you go to,’” Wilson said. “But I was frankly thinking about it the wrong way. You have multiple representatives to help with the endeavors ... that the cities are facing.”

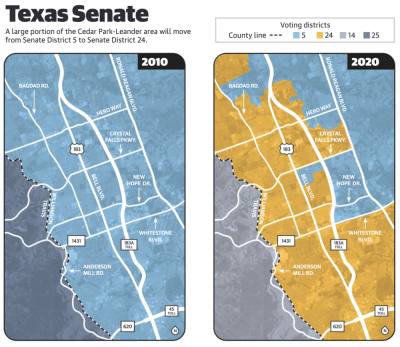

In the state Senate, District 24 will primarily represent Cedar Park and Leander with District 5 covering some western areas and District 25 covering the Travis County portion of the cities.

The new District 24 includes most of Cedar Park and Leander and stretches from Bell County to south of San Antonio and to Sutton County in central West Texas. District 24 incumbent Sen. Dawn Buckingham, R-Lakeway, is running for Texas Land Commissioner, and three Republican candidates are vying for the seat.

District 5 Sen. Charles Schwertner, R-Georgetown, previously represented all of Williamson County in addition to other Central and East Texas counties. Schwertner is running unopposed for reelection.

Albert said these particular state senate districts are an example of maps drawn for political purposes and do not create “communities of interest” as someone in Cedar Park would have little in common with a resident in rural Sutton County. Some people or groups testified to lawmakers in favor of keeping communities together rather than divided.

“There were some interesting back and forths of people drawing the maps arguing ‘you’re better off being sliced into two districts because you get two representatives representing you rather than one,’” Albert said. “But typically that’s not really what they want. They want somebody who represents your entire community and its interests rather than someone who has you on the margins of their community or half of your community.”

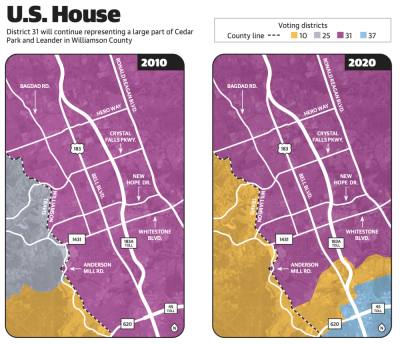

In the U.S. Congressional districts, District 31 Rep. John Carter, R-Round Rock, will continue representing a large part of Cedar Park and Leander in Williamson County, if reelected. But some residents will now be in District 10, which stretches from areas west of Houston to western Travis County—connected by a narrow area of south Cedar Park.

The redistricting process also redrew maps for the State Board of Education. In old maps, the Williamson County portion of Cedar Park and Leander was represented in District 10. New maps have divided the Travis County portion and the southern Williamson County portion into District 5, whose incumbent Rebecca Bell-Metereau, D-San Marcos, is running for reelection in the Central Texas district. The remainder of Williamson County remains in District 10, which is represented by Tom Maynard, R-Florence, who is running unopposed.

Redistricting is also done at a local level. Remapped Williamson County commissioner precincts went into effect Jan. 1, though a majority of the Leander-Cedar Park area remains in precinct 2. Travis County commissioners also approved new maps, and the local Travis County area will remain in precinct 3. However, Cedar Park and Leander city councils are elected at large without geographic districts, so redistricting is not needed like in the neighboring cities of Austin or Georgetown.

Contesting redistricting outcomes

This year also marked the first year in which Texas was not under preclearance, according to the state's redistricting website. Preclearance was a provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that required states with a history of racial discrimination against voters from minority communities to submit their maps for federal approval. The United States Supreme Court eliminated preclearance in 2013.

The process of creating the maps in the Texas Legislature brought resistance from various groups concerned the process would not result in an equitable reflection of where new population growth occurred in the state, said Miguel Rivera, voting rights coordinator for the Texas Civil Rights Project.

“So we know that in Texas over the past 10 years, the state’s population grew by 4 million people and that 95% of that growth was from people of color. The maps at both the congressional level, the state Senate and even the state House level, don’t actively increase the districts that represent these new communities, but instead, actively increase majority Anglo districts in the map’s representation,” Rivera said.

Those allegations are in line with a U.S. Department of Justice lawsuit brought against the state of Texas on Dec. 6 alleging “vote dilution,” or spreading voters of color around several districts to reduce their voting power. If that could be proven in court, it would be a violation of Section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, according to the lawsuit.

“I think there was a tactic as a part of a larger strategy that we saw in gerrymandering from the state government this time around. I think the last time [in the last redistricting process] we definitely saw the cracking of urban centers. But I think this time around as urban centers grew by so much and basically grew too big [and were split] into several districts,” Rivera said.

Albert said if fair representation is wanted that reflects communities of interest, keeps communities together, produces representation that looks like the population, then a different model that doesn’t allow current lawmakers to protect incumbents and partisan advantage. Independent redistricting commissions could create fairer models and more neutral maps, he added.

“Most people don’t pay attention to this process,” Albert said. “Whoever gets to draw the lines determines a lot about who has political power in this state.”

Jishnu Nair and Eric Weilbacher contributed to this report.