That number is expected to surge as more residents find themselves unemployed as a consequence of the host of layoffs and business closures caused by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Since March 11, unemployment claims peaked for the period spanning March 18-April 18, totaling 6,582 claims in the five Tomball and Magnolia-area ZIP codes, according to the Texas Workforce Commission.

“That was before the layoffs, so now the phones are ringing off the hook. We’ve had to streamline our process and move it online to start accommodating the number of people who are now without insurance who live within our service area, and they’re finding out TOMAGWA is their only option,” Simmons said.

TOMAGWA provides care to those ineligible for or unable to access health insurance throughout portions of Harris, Montgomery and Waller counties, she said.

In Tomball and Magnolia, the only other option for uninsured residents seeking care is an emergency room, Simmons said; however, the area’s only hospitals are located along the Hwy. 249 corridor, miles from TOMAGWA’s western limits.

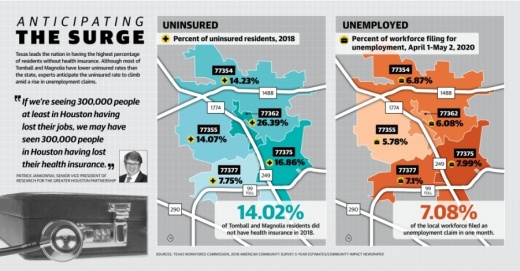

More than 22,400 residents within the five Tomball and Magnolia ZIP codes are uninsured, according to 2018 five-year estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau, which totals 14% of the population.

As Texas had the highest percentage of uninsured residents nationwide in 2018, policy leaders point to Texas’ hesitancy to expand Medicaid eligibility—as outlined by the Affordable Care Act—as a likely contributor.

“I do think the current situation really changes the playing field [for Medicaid expansion] for a variety of reasons,” said John Hawkins, senior vice president for advocacy and public policy with the Texas Hospital Association. “This [legislative] session [in 2021] would be a really good chance to tee that issue up again.”

Counting the uninsured

Census estimates show Texas had the highest percentage of uninsured residents in the U.S. in both 2013 and 2018 with 17.4% of Texans, or 4.76 million residents, uninsured in 2018, down from 22.8% in 2013. By comparison, the U.S. rate totaled 9.4% in 2018.

“One of the challenges we have in Texas is we’ve got a lot of small businesses, a lot of independent contractors. These businesses struggle to provide health insurance. If you’re an independent contractor, it’s hard for you to be able to afford health insurance,” Hawkins said.

In addition to not having expanded Medicaid, Texas also has the second-highest noncitizen population behind California, with nearly 1.46 million uninsured noncitizens in Texas, according to 2018 census estimates.

Simmons said many of her patients are among the retail and food service workers as well as small businesses for which paying for or providing health insurance is difficult, particularly as the pandemic lingers.

“Most of our patients are in those industries who had to do the layoffs, and so they are finding themselves without insurance—or even before [the pandemic] they could not afford it so they relied on safety-net clinics like TOMAGWA,” Simmons said.

As unemployment claims surge, a higher uninsured rate is expected to follow, said Lynn LeBouef, the CEO of the Tomball Regional Health Foundation.

“Certainly the uninsured population is growing. We have a whole lot of people that have been furloughed because of COVID-19,” he said. “I don’t think we have seen the full impact of the uninsured population yet in our area.”

TWC data shows 2.1 million unemployment claims were filed in Texas between the weeks ending March 14 and May 16 as of press time.

Locally, about 7% of the labor force in Tomball and Magnolia filed for unemployment in the month spanning April 1-May 2, although unemployment claims peaked the month spanning March 18-April 18, according to census and TWC estimates.

“If we’re seeing 300,000 people at least in Houston having lost their jobs, we may have seen 300,000 people in Houston having lost their health insurance,” said Patrick Jankowski, senior vice president of Research for the Greater Houston Partnership, in a May 12 webinar.

Care during COVID-19 outbreak

To prepare for an influx of uninsured residents, Simmons said TOMAGWA moved its enrollment process online in late May. Patients can fill out forms to be approved virtually, and then health assessments will be done. Previously, clients had to have lengthy visits with TOMAGWA to become a patient, she said.

Simmons said caring for the uninsured is particularly difficult currently because of limited funding, a lack of personal protective equipment and few COVID-19 testing resources close by for the uninsured population. Simmons said TOMAGWA has not been able to access COVID-19 testing kits, perhaps the largest need in caring for the uninsured community.

“That’s the big issue,” she said. “As a safety-net clinic we are not on any list to receive COVID-19 tests, so we have to get out there and fight just as an individual practice to get access to the tests.”

Some testing sites have been set up around Harris County, with Harris County Public Health’s mobile sites visiting Tomball in April and Creekside in May. Montgomery County also rolled out a voucher-based program May 13 in which county residents could register for a free test in The Woodlands or Conroe. However, Simmons said not having transportation is the No. 1 barrier for the uninsured population to receive health care.

“Without them having the resources—the money to pay for tests—without them having their safety-net clinic being able to provide the test, you have this large population of people who are not tested who can be spreading the virus and making it worse,” Simmons said. “I think that will continue to be a barrier in our ability as counties to manage the spread because we have not made it accessible for uninsured residents in the rural areas to have consistent access to testing.”

Expanding Medicaid

According to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation—an independent health care information nonprofit—1.5 million uninsured nonelderly adults in Texas could be covered if the state expanded Medicaid eligibility. Policy leaders anticipate this could be more amid recent job losses.

“If we were to do Medicaid expansion right now, we would not only pick up a million and half of those adults who are already uninsured, but potentially, the million or more who may have found themselves on the uninsured rolls in the last month or so would have an option,” said Anne Dunkelberg, associate director of the Austin-based Center for Public Policy Priorities.

Most residents living in states that have expanded Medicaid and earn less than 138% of the federal poverty level are covered, according to the foundation. In Texas—a nonexpansion state—low-income individuals who are pregnant, a parent or relative caretaker of a child under age 19, have a disability or a family member in the household with a disability, or are age 65 or older may be eligible for Medicaid, according to Texas Health and Human Services. But not all low-income individuals are covered.

Hawkins said while many states have expanded Medicaid with no strings attached, more politically conservative states have opted to expand with a working requirement or a small out-of-pocket payment—flexibility that comes via states using a Section 1115 Medicaid waiver to expand eligibility.

“It’s almost going to be super subsidized, but even if it’s a $5 a month premium, their argument is at least now folks have some skin in the game,” he said. “That’s good for beneficiaries to have skin in the game because then they’re going to show up to appointments; they’re going to be better utilizers of health care.”

State Rep. Tom Oliverson, R-Cypress, an anesthesiologist, said while he anticipates Medicaid expansion will be discussed in the state’s upcoming legislative session—slated to resume Jan. 12—he anticipates redistricting, unemployment and fiscal matters will get more of the focus.

“The question is, philosophically, whether or not it’s appropriate for the state government to be providing free- or reduced-cost health insurance for able-bodied adults who don’t currently have coverage through their employer,” he said. “I actually think that the biggest problem we have with health care in Texas is not the availability of health care; it’s the affordability of health care. ... That’s not necessarily a problem that Medicaid is designed to solve, because if ... you expand Medicaid all you’ve done is basically changed who’s paying the bill.”

Oliverson said concerns with the traditional expansion of Medicaid include that not all Texas physicians accept Medicaid and that expansion could be costly for the state, particularly amid the pandemic and economic downturn.

“While I do think that there’s going to be a strong conversation about health care, ... traditional Medicaid expansion like a lot of my colleagues like to talk about requires a match, and we’re not going to have any money for a match,” he said.

However, Dunkelberg said she believes the ongoing pandemic changes the Medicaid discussion.

“The shape of this disaster may help ... because you have literally millions of Texans who maybe have never been jobless before suddenly overnight being thrown into that situation,” she said. “So when millions of Texans suddenly discover that because they have no income, they don’t qualify for anything, you may have a change in the political pressure [about Medicaid expansion].”

Adriana Rezal and Hannah Zedaker contributed to this report.