During the coronavirus outbreak, counselors and other service providers tune in while staying home to serve clients of the LGBTQ-focused center who need a safe place for care.

“Some people are not out at home, and so they’re not comfortable because they don’t have private space to use the phone or a computer,” Communication Manager Austin Davis Ruiz said.

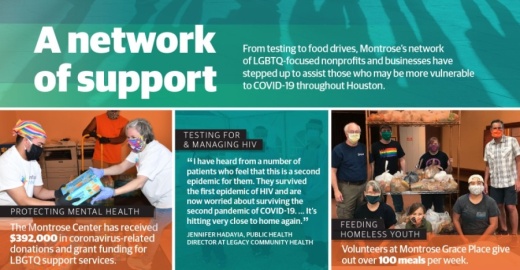

The unique approach offered by the Montrose Center is one of many innovations LGBTQ-focused organizations in the area are using to meet the needs of clients during a time when stressors and health disparities are disproportionately affecting vulnerable communities. With the community’s biggest rally, Pride Houston, now postponed to the fall, Montrose-based LGBTQ support services are adapting to coronavirus-related disruptions.

“It’s important to have LGBT-affirming services because a lot of our clients have sought services where they are met with a lot of disdain for our community,” Davis Ruiz said. “They want people who ... are sensitive to their needs.”

Social pressures

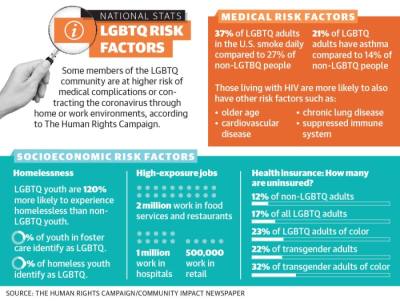

Efforts to curb the spread of the coronavirus are compounding the challenges some members of the LGBTQ community were already facing.

While staying home to curb the spread, some are at higher risk of facing domestic violence.

According to data from the Harris County Sheriff’s Office, while calls related to domestic violence saw an overall 10% decrease between the months of January and February, that number shot back up in March by 20% with 1,558 domestic violence-related calls reported countywide.

“People are forced into situations where they are not in a safe environment,” Davis Ruiz said.

By the end of April, Houston Police Department Chief Art Acevedo said assault calls, often related to domestic disputes, were up 9% since Harris County’s stay-home order went into effect March 25. In the same time period, the Montrose-based Houston Area Women’s Center’s hotline call volume increased 40%, said Emily Whitehurst, the center’s president and CEO.

Such pressures can push LGBTQ youth into homelessness, said Courtney Sellers, the executive director of youth service provider Montrose Grace Place.

“Really any marginalized group of people tends to get left behind in the decision-making for an entire society,” Sellers said. “They’re not often at forefront of decision-makers’ minds, so we create that space for them and saying we’re thinking about you and we understand the issues you’re facing.”

Sellers said many who seek services from Montrose Grace Place work in some of the industries hardest hit by coronavirus shutdowns.

“A lot of the concerns I hear from the youth right now are the same difficulties we see elsewhere,” Sellers said. “They’re being laid off or their hours are reduced, and they are unable to file for unemployment.”

Data from advocacy group The Human Rights Campaign Foundation suggests as many as 2 million LGBTQ adults, or 15% of the total LGTBQ population in the United States, work in the food service industry, making them more likely to lack quality health insurance, paid sick leave and stable wages.

These types of increased stressors can lead to higher rates of addiction as well, said Martin Sunday, the board chairman of the Lambda Center, a Montrose-based addiction recovery center focused on the LGBTQ community. For those in recovery, the most difficult aspect of the pandemic is social distancing measures.

“Loneliness is what causes relapse quite often,” he said.

Living at risk

Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, many members of the LGBTQ community faced outsized health and safety risks in addition to barriers to quality health care. Now, Houston’s own coronavirus hospitalization and death rates are showing poorer overall health makes the virus harder to beat.

“Research has shown that people who are same-gender-loving and transgender-identified face discrimination in the health care system,” said Jennifer Hadayia, the public health director of federally qualified health center Legacy Community Health. “If we don’t have supportive spaces for them, they may defer their care and become sicker and become more isolated.”

Hadayia said some members of the LGBTQ community feel they are managing two pandemics at once.

“I have heard from a number of patients who feel that this is a second epidemic for them,” she said. “They survived the first epidemic of HIV and are now worried about surviving the second pandemic of COVID-19. ... It’s hitting very close to home again.”

Dr. Jennifer Feldmann, a physician at the Montrose clinic said they have been focusing on keeping in contact with those on and who want to start HIV-preventive medications.

“Unfortunately, those who are dying from COVID-19 tend to be people who are people of color and people of lower socioeconomic status,” Feldmann said. “And we saw the same thing with HIV.”

Reaching out

In the face of these uncertainties, Montrose remains the physical epicenter of Houston’s LGBTQ outreach services, even if those seeking them come from all over the city.

For the Montrose Center, an organization that serves thousands of people per year, suspending in-person accommodations meant staffers needed to find new ways to reach clients.

“When we closed our senior diner down, we transitioned to providing a box of shelf-stable meals to our seniors,” Davis Ruiz said. “We’re still trying to make sure to provide service and care and bring that support.”

The Montrose Center has also been able to restart support groups virtually for youth clients and bring HIV testing into the community rather than on-site, Davis Ruiz said.

Similarly, the Lambda Center launched a virtual hangout room that allows people to congregate in lieu of in-person gatherings. Sunday said feedback has been positive.

“In a way, we kind of have a leg up on the rest of the world right now,” Sunday said. “We’re already getting through the crisis we’ve had in our lives that it took for us to get sober and stay sober.”

By shifting to virtual support groups, several providers said they have even seen increased participation and will continue the practice in addition to in-person events when possible.

“We used to get excited when we had a vogue night at our engagement center and five people would show up,” Hadayia said. “Now we do a virtual Q&A on voguing and we have 20 people show up. ... We’re keeping people socially connected in a way we weren’t able to before.”

Colleen Ferguson and Hannah Zedaker contributed to this report.