As the end of 2021 approaches, Smith said she is still struggling with equipment delays and supply shortages that have made it difficult to estimate when the eatery will open.

“We just keep getting pushed back,” Smith said. “I ordered a three-compartment sink months ago and have no idea when it may or may not come in.”

Supply chain scarcity, delivery delays and rising costs have taken a toll on consumers and business owners as industries continue to grapple with coronavirus-related restrictions and shipping backlogs.

Facility closures and lockdown measures during the early months of the coronavirus pandemic contributed to stalls in the production and rising costs of many consumer goods, according to a report from the American Farm Bureau Federation.

“The public gets frustrated when they go to [the store] and they’re limited to two packs of chicken wings,” Smith said. “Well, we’ve been dealing with that now since last August.”

As the holiday season approaches and suppliers anticipate demand for goods to increase further, Smith said the current high costs and shipping delays are likely to persist.

Supplies dwindle under COVID-19 restrictions

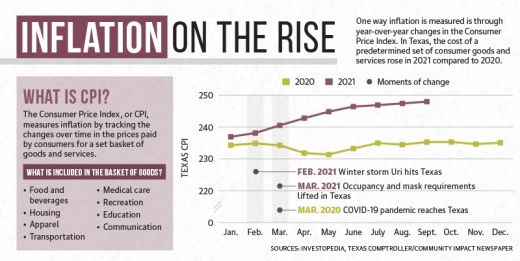

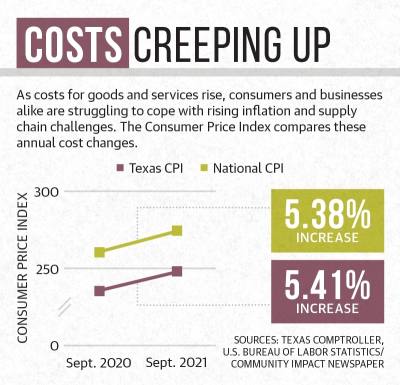

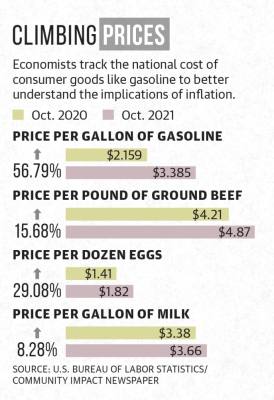

In October, the Consumer Price Index rose 6.2% year-over-year in the U.S., accounting for the largest increase since November 1990, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Consumer Price Index, or CPI, measures inflation by tracking changes in the prices of a set selection of goods and services that are determined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Goods like food and gasoline are included in the CPI market basket.

In Texas, the CPI rose 5.41% in September compared to 2020, according to the Texas Comptroller.

While many factors contribute to inflation, Sam Tenenbaum, an economist with CoStar Group, said factory closures and global shipping delays caused by the coronavirus pandemic kickstarted the recent wave of issues.

“A lot of the price increases are sort of the domino effect of the [COVID-19] supply chain issue,” Tenenbaum said. “A lot of the manufacturing operations can’t stop on a dime, and then turn around and restart operations at full capacity in a few weeks.”

During lockdowns instituted early in the pandemic, many manufacturing facilities and shipping hubs were temporarily closed, Tenenbaum said.

“We all sort of expected the economy to weaken considerably and consumer spending to go down,” Tenenbaum said. “But that didn’t really happen, because the federal government stepped in and provided a stopgap measure to get us to the other side of the pandemic.”

While spending on services like haircuts and travel did drop, federal stimulus funds and increased unemployment benefits led to a rise in demand for consumer goods.

As the manufacturing and trade industries reopened, demand rapidly outpaced supply and exacerbated shortages, Tenenbaum said. Delivery times from country of origin to market have also increased significantly, said William Chittenden, associate professor in the McCoy College of Business Administration at Texas State University.

“In 2019, the end-to-end transit time between China and the U.S. was 40 days. And today, it’s almost twice that—73 days,” Chittenden said.

Plastic products became scarce, said Madison Monaco, chef at Sylver Spoon restaurant in New Braunfels. When Monaco could find the equipment and supplies she needed, they were often significantly more expensive than before the pandemic.

A drink machine Smith ordered in May was not delivered until October because of equipment and labor shortages, she said.

Businesses adapt

As product prices have risen, business owners like Monaco said they have made changes to their services in an effort to mitigate costs.

“We’ve changed up the menu a little bit so it is still fine dining but a little bit cheaper margin for us,” she said. “I noticed myself being a lot more worried about food every second.”

Seana Rousseau, owner of The Chain Link Bicycle Shop in downtown New Braunfels, said she has a backorder of bicycles that continues to grow with only a few trickling in at a time.

“I still have 70 bikes on backorder from last October,” Rousseau said. “I’m getting two at a time, maybe.”

Rousseau said the issue is similar with bicycle parts and accessories, such as tubes and tires.

“I’ve started stocking stuff that I wouldn’t have bought before... I’m just filling in the gaps with whatever I can,” she said.

Increases in manufacturing delays also prompted increases in wholesale prices. An average price of $400 per bicycle is now up to around $600—a 50% increase. It is difficult to justify passing that increase over to the customer, Rousseau said.

“I ordered a higher-end bike for someone that took me 9 months to get. It was around $5,000 ... The retail price went up as well as my cost but I [had] already sold it to him... I lost $600 on that one,” she said.

Preparing for continued delays

Price hikes and shipping delays are anticipated to continue through the new year as demand ramps up during the holiday season and major industries struggle to find labor, according to estimates from the Federal Reserve.

The Federal Reserve is responsible for conducting national monetary policy, supervising and regulating banks, maintaining national financial stability and providing banking services.

The long-reaching effects of the pandemic and ensuing supply chain issues experienced are likely going to require business owners and consumers to adjust their spending and expectations, Smith said.

Smith said she is still unsure of when she will be able to open the New Braunfels location of Lucy Cooper’s Texas Ice House, and other area businesses will likely continue to encounter supply chain delays, she said.

“It’s not just about the virus anymore. It’s about the cause and effect of this that is created,” Smith said. “We’re all having to look at the challenges that we have and come up with an opportunity that works for each individual business owner.”

Carson Ganong contributed to this report.