When power lines likely collided into each other resulting in sparks, according to an August 2012 report from the Travis County Fire Marshal’s Office, what started as a brush fire quickly grew to engulf 6,500 acres, destroyed more than 60 structures and burned for 11 days before being extinguished Sept. 15, 2011.Since then, new homes, businesses and other structures built in the Steiner Ranch area and Central Texas coexist with the vast acreage of the Balcones Canyonlands Preserve—a 50-square-mile tract created in 1996 that continues to loom as a wildfire threat.

In western Travis County and Northwest Austin, two of the areas in Central Texas that are at the highest risk of wildfire, professionals continue working to diminish danger.

From creating what are called shaded fuel breaks in areas of high vegetation such as greenbelts to boosting educational outreach, the goal for area firefighters and officials is to ensure the 2011 fire never happens again.

Assessing wildfire risk

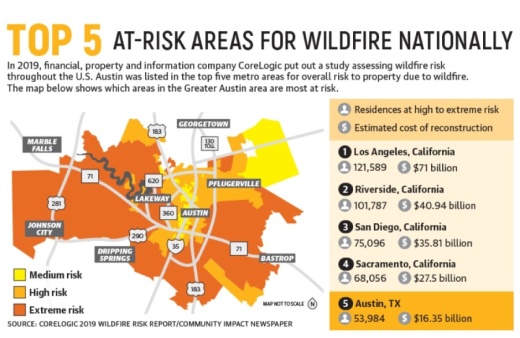

In 2019, financial, property and consumer information company CoreLogic put out its national Wildfire Risk Report. Among the findings, the Greater Austin Metropolitan Statistical Area was found to have the fifth highest risk in the nation with regard to a large-scale wildfire incident.

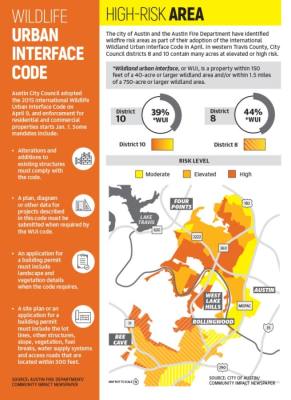

In the report, Austin was listed as having 53,984 residences labeled as high to extreme risk for wildfire. Because of these dangers and several other factors, Austin City Council voted April 9 to approve the 2015 International Wildland Urban Interface Code, or WUIC. According to the city of Austin website, that makes Austin the first major city in the state to adopt such a code, and implementation is slated to begin Jan. 1.

Once implementation of the code begins, the main focus remains construction of ignition-resistant structures, of which more than 60% are found within 1.5 miles of the Wildland Urban Interface, according to Austin Fire Department Division Chief Tom Vocke.

“We have focused on enhanced construction as our primary push in this first adoption of the new WUI code,” Vocke said in an email, adding there will be no impact for most on the

Jan. 1 start date, save for those building or remodeling a portion of their home’s exterior. “[WUI code enforcement for] all aspects will begin

Jan. 1 for all new projects moving forward from that date, [and] projects already in progress will not be affected.”

In the meantime, communities in western Travis County have been ramping up their efforts to reduce risk.

“I think what Austin did by approving that WUI, that’s a great start,” said Chris Rea, wildfire mitigation specialist for Lake Travis Fire Rescue.

Rea said the code is more specific to requirements for residential landscaping, such as the distance between trees in yards, for example, but he added it is a step in the right direction.

In communities such as Steiner Ranch, Rea conducts home assessments, during which he meets with homeowners to give them a checklist of tasks they can complete to harden their homes against wildfire.

There are thousands of fire entry points within a home, such as roof vents and gutters, and knowing the risk is key to protection, he said.

“Most people, I think when they think of wildfire, they picture what we often see on TV, which is flames just blazing through the forest,” Rea said. “That’s actually not what burns most homes down. Ninety percent of homes burn down from embers that can travel up to a mile.”

A needed increase in educational outreach

Doolittle considers herself lucky that her home did not burn down in the 2011 Steiner Ranch fire.

That day in September 2011 just before she noticed the fires, she ran errands—to Costco and to pick up Chinese food, among others. As she pulled back into Steiner Ranch, she said she surveyed the Hill Country view and could see smoke.

Shortly after that, she learned through a neighbor there was an evacuation order in place. She and her family packed as much as they could, trudged through crawling traffic out of the area and stayed with friends in South Austin for several days.

Unprecedented drought conditions and rapidly drying vegetation created perfect conditions for fire to spread.

Gov. Rick Perry declared the wildfires that spread through Pedernales and Steiner Ranch on Sept. 4 disasters. In the Steiner Ranch area alone, 23 homes were destroyed. Doolittle said thankfully, hers was not one of them.

Doolittle became chair of the Steiner Ranch Firewise Committee in 2015 and wrote articles, mostly for the neighborhood newsletter called the Ranch Record, trying to engage the community on the importance of fire safety. She also performed home ignition zone inspections as much as possible.

The No. 1 thing that struck her during her 3 1/2 years as chair of the Firewise Committee, she said, was the challenge of generating enthusiasm for risk prevention.In 2019, Doolittle met Steiner Ranch resident and retired engineer Bill Hamm, who took over as chair of the committee in January.

Hamm and other Steiner Ranch residents are now serving on the Firewise Committee, educating residents and conducting home ignition zone inspections.

Nine other Northwest Austin neighborhoods have also been recognized by the national Firewise program: Canyon Mesa, Courtyard, the Estate at the Overlook, Greater Valburn Circle, Jester Estates, Long Canyon, River Place, Meadow Mountain and Versante Canyon.

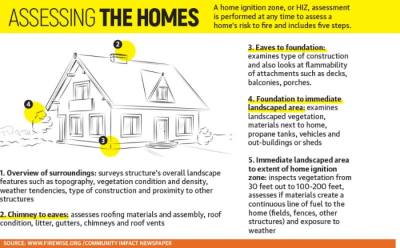

During the Firewise inspections at Steiner Ranch, home ignition zone assessment is performed to check a home’s risk to fire and includes several steps, according to Firewise USA, an organization designed to help communities reduce fire vulnerabilities within their homes and other structures. The assessments include an overview of a property’s surroundings as well the vulnerability of the property itself.

Hamm said there is still much work to be done in the Steiner Ranch neighborhood with regard to assessments within the community, and the Firewise Committee is hoping for a risk assessment from Lake Travis Fire Rescue by the end of the summer.

When Doolittle chaired the committee, she was able to conduct four or five inspections a year, Hamm said, and now that there are more members in the committee, they have seen an increase in homeowners having signed up for the inspections since fall 2019.

“With 4,500 homes or so [in Steiner Ranch], that’s a drop in the bucket,” Hamm said.

Safeguarding the wildlife

In the Balcones Canyonlands Preserve, an area in western Travis County taking up more than 32,000 acres, some of which abuts the Steiner Ranch neighborhood, the predominant vegetation consists of juniper oak, what many in this area refer to as cedar.

This is according Johanna Arendt, community liaison for Travis County’s Natural Resources Program, who said that it is a common misconception that juniper trees are more prone to wildfire than other flora.

In truth, she said, juniper trees are full of moisture much of the time and therefore difficult to catch on fire.

Arendt, who works primarily in the BCP, pointed to a 2014 study from Baylor University that found oak-juniper woodlands should be considered a low fire risk because, under normal conditions, they can withstand low-intensity surface fires that are most common in Central Texas.

A much more prevalent cause of spread, Arendt said, is the grasses that lie underneath the trees.

“The 2011 Steiner Ranch fires were kind of a perfect storm of high wind and low moisture because we’d been in a drought for such a long time [at that point],” she said. “It caught grasses on fire first, and then the trees. You get a ground fire that then goes up into the canopy, and because the canopy has more fuel, then you get these big fires with embers that waft.

”Like Rea, Doolittle and Hamm, Arendt said embers are the biggest danger to homes near wildlife areas and wildfire.Under current conditions, Arendt said the BCP is not in as much risk as it was in 2011, but she added she does not want to downplay the importance of education and mitigating risk.

For Arendt and others who manage wildlife preserves, specifically the BCP, workers focus on fuel reduction, primarily through a technique called shaded fuel breaks, which are different from normal fire breaks.

“[Traditional fire breaks] are not what we want here, because when you do that, generally grass grows up and that is what is most likely to ignite.” she said.

To create shaded fuel breaks workers will, to some extent, thin out the juniper trees but keep the canopy they create intact because the shade keeps the grasses and finer fuels on the ground from regrowing, she said.

Generally, shaded fuel breaks are executed along the border where green spaces meet development and can continue roughly 100 feet or so into the wildlife areas, Arendt said, adding that is where the highest risk for wildfire is.Arendt said county workers team up with groups such as Texas Conservation Corps, the Austin Fire Department, Lake Travis Fire Rescue and the Steiner Ranch Firewise Committee.

Arendt said county crews will begin creating shaded fuel breaks in the BCP in September. The nesting season for the golden cheeked warbler, a protected species within the preserve, concludes at the end of August.Fuel mitigation work is done every fall and winter, and so far her team has conducted shaded fuel breaks along 4.8 miles of the boundary between Steiner Ranch and the BCP.

“It is something that we take very seriously and need to prepare for,” she said. “We do, and that’s why we do these projects every year and have been since 2011.”