In 2016, 10 years after she graduated from The University of Texas at Austin, then-Austin resident Jenny Sanzo and her husband, Evan, wanted to stop renting and buy their first home.

At an entry-level price point of $200,000, Sanzo, who works downtown as an accountant for the Office of the Attorney General, said their Realtor only found two options in Austin—each one run down and in need of extensive repairs.

The first-time homebuyers broadened their search to Pflugerville where they settled on 1,400-square-foot, two-story, three bedroom, two-and-a-half bath home for $190,000. Sanzo said the home, which was less than four years old, was exactly what they were looking for with only one exception: her commute would be 45 minutes in each direction—a round trip she has now been making for two years.

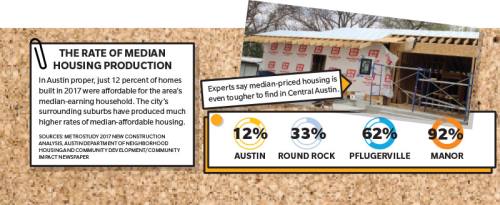

Local housing experts say Sanzo’s story reflects a common thread for middle-class families who work in Austin. Under the pressures of the city’s affordability crisis, Austin’s working families are moving out to suburbs such as Pflugerville, Round Rock and Manor, where housing prices are cheaper but work commutes are longer.

The market challenges are acutely felt in Central Austin, where neighborhoods once characterized by single-story bungalow starter homes now boast median home prices near $1 million, according to recent housing data. The area has become financially inaccessible to many of the metro’s middle-class families, while rising property values place financial burden on existing homeowners who have watched their home values—and property taxes—double in the last decade.

According to metrics used by the city of Austin, housing is considered affordable when a household spends 30 percent or less of its income on housing costs, including utilities. Households that spend more are considered cost-burdened.

By that standard, the average two-person Austin household, earning the area’s median income of $65,100, falls well short of what is needed to afford the median home price in Central Austin, according to mortgage calculations.

Some community members say they do not see a future where middle-income affordable homes will be built in Central Austin, but city officials recognize a need to keep middle-income families.

“If someone is a part of our community, they should be able to live in our community,” said Jonathan Tomko, principal planner with the city of Austin.

The city has wrestled with the affordability crisis for years, but officials say 2018 has the potential for major strides with the potential approval of a new land-development code through CodeNEXT and an upcoming November election for what could be the largest affordable housing bond package in city history.

What is to blame?

Tomko attributed the housing affordability challenges to two main factors. He said although the city could not control the effect of more affluent people moving to Austin and placing upward pressure on housing unit costs, the city could better control the supply and demand.

Tomko points to the 2008 recession as a major contributor to the city’s lack of adequate housing supply. He said because of the credit crunch between 2009 and 2013, banks were not lending much to developers, which slowed housing production by roughly

80 percent, even as the city’s population continued its pre-recession growth.

“While there is a lot of development ... now, we are honestly just getting caught up with what we should have been building during that time,” Tomko said.

Emily Blair, executive director for the advocacy group the Home Builders Association of Greater Austin, said builders want to meet the large demand for the middle-income home price point in Austin, but land prices and increased costs in labor and materials make it difficult.

“Central Austin just doesn’t have that much available land, and the value of the land alone far exceeds the median home price,” Blair said.

David Whitworth, owner of Whitworth Homes, has been building homes in Central Austin since 2004. He said he prefers to build smaller, less expensive homes as they sell quickly, while $1 million homes often sit on the market for a year. However, Whitworth said restrictions on minimum lot size in Central Austin neighborhoods make the smaller homes more difficult.

Proposals to subdivide large, expensive lots in order to build smaller, less expensive homes—commonly referred to as “missing middle housing”—require a long permitting process and often receive heavy pushback from the neighbors, he said.

“I want to deliver houses to young families, but our [land development] code is trending toward the million-dollar home,” Whitworth said. “Our code makes the wrong product easier and does not even allow [a middle-income] product.”

Jeff Jack, president of the Austin Neighborhoods Council, a group that strongly opposes added density in Central Austin neighborhoods, said allowing more housing types in the neighborhoods would only create more housing opportunities for the wealthy and continue to push existing homeowners out.

Jack said because Central Austin real estate is so desirable, market demand and competition between buyers will continue to bid up the prices, especially as Austin continues to attract a wealthy economy.

“[Dense housing] will still be unaffordable for moderate- or low-income people,” Jack said. “You can’t build an affordable home in the Zilker Neighborhood … not until we have the next economic downturn.”

Limited avenues for government intervention

Tomko said the Legislature has made it difficult for local government to intervene in the housing market.

Texas is one of three states that prohibit inclusionary zoning—a tool that allows municipalities to mandate affordable housing from private developers. Tomko said Texas cities also have no option of creating rent control districts—unless the governor calls for a state of emergency—and last year, the Legislature voted to ban linkage fees, a program that would have linked new development to affordable housing funding.

However, the runaway real estate market has forced the local government to innovate several counter-market measures over the years. The latest push looks to take advantage of a 10-year housing plan, a new land-development code proposal, public funding and a handful of fresh ideas.

The third iteration of CodeNEXT, released in February, introduced a money-saving permitting process and an expanded density bonus program—an affordable housing tool that allows City Council to trade building entitlements for income-restricted housing commitments and other community benefits.

The latest draft incentivizes the preservation of existing market-affordable housing, and increased housing entitlements along the city’s transit corridors aim to produce enough supply to relieve the interior neighborhoods of demand pressures.

Should City Council approve, in November Austinites will vote on an $851 million bond package—a 30-year loan paid off by tax dollars—to fund city projects. The current recommendation has $161 million earmarked for affordable housing initiatives, the largest such bond allocation in city history, according City Council members.

Tomko said the city should expand its use of the underused tax increment-financing program. Publicly funded capital improvements—such as the mobility bond projects—can result in increased property values and have unintended consequences, Tomko said. To mitigate the economic burden, the city can take the tax increase money and reinvest it into affordable housing in the affected area. Tomko said the program is widely used in Dallas, Houston and San Antonio.

In March City Council made a push to vet city-owned land for affordable housing use and explore a program that could bring back people displaced by the pressures of new development.

For Sanzo, although she once hoped to own a home in Austin, she has warmed up to the suburban life.

“To be honest, now that we’re living here, we really love Pflugerville,” Sanzo said. “But I would hope that someday I can live closer to where I work.”